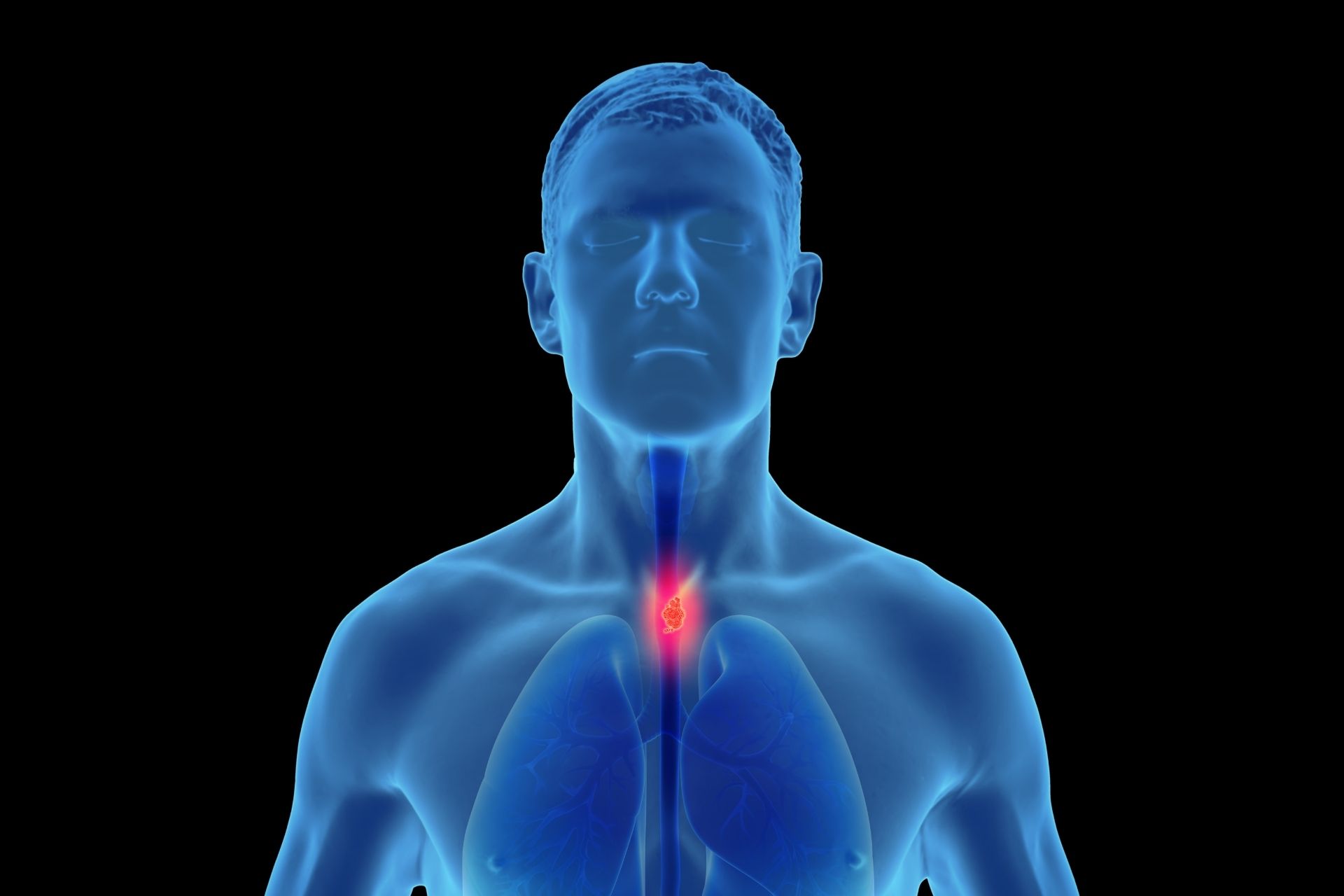

Oral health problems are linked to a higher risk of esophageal cancer, which kills about 445,000 people every year. Now, researchers have found that certain harmful microbes in the mouth appear to promote cancer development, while others might help protect against it.

The findings, published in Cell Reports Medicine, suggest that disruptions in oral microbial balance may partly explain how poor oral health contributes to esophageal cancer.

Scientists have known that the oral microbiota may play a role in esophageal cancer, as imbalances can trigger inflammation and other changes that contribute to cancer. However, more human studies are needed to understand how oral microbes influence cancer risk.

To examine how oral health and the oral microbiota interact in cancer risk, researcher led by Peipei Gao at Fudan University in Shanghai, China, analyzed saliva samples from 206 people with newly diagnosed esophageal cancer and 206 healthy controls.

Poor oral health

The researchers found that poor oral health—such as losing teeth after age 20, having many missing or filled teeth, not using dentures, and brushing teeth infrequently—was linked to a higher risk of esophageal cancer.

People with esophageal cancer had less diverse and less rich microbial communities in their mouths compared to healthy individuals. About 60 microbial species differed between the two groups, with harmful bacteria linked to gum disease, including Prevotella, Treponema, and Porphyromonas, being more common in people with esophageal cancer, while beneficial microbes such as Neisseria were reduced.

In people with esophageal cancer, the team also found changes in the metabolic activity of oral microbes, including altered amino acid, carbohydrate, and energy metabolism.

Targeted interventions

Some microbes, including Campylobacter rectus and Eubacterium brachy, could explain a significant portion of the link between poor oral health and esophageal cancer. Low levels of Streptococcus mitis, a common bacterium in the mouth, increased the risk of esophageal cancer in people with poor oral health, while higher levels appeared to mitigate it, the researchers also found.

S. mitis produced short-chain fatty acids and other compounds that suppress harmful bacteria. The microbe also survives the acidic environment of the esophagus and stomach, where they may interact with tissues to influence cancer risk, the authors say.

The findings, they add, “highlight the promise of precision-targeted microbial interventions to improve oral health for [esophageal cancer] prevention and management.”