• Protective bacteria

• Fat metabolism

What is already known on this topic

Several studies have shown that changes in the gut microbiota composition can play a role in the development of Parkinson’s disease. But how gut bacteria affect this neurodegenerative disorder remains unclear.What this research adds

In a worm model of Parkinson’s disease, researchers showed that Bacillus subtilis microbes can slow—and even reverse—the build-up in the nerve cells of alpha-synuclein, a protein associated with Parkinson’s.Conclusion

The findings could inspire drug therapies based on protective bacterial metabolites or diet-based interventions that alter the gut microbiota composition, the researchers say.

An estimated seven to 10 million people worldwide have Parkinson’s disease, a progressive brain disorder that affects movement. A new study in worms suggests that a common gut microbe could slow—and even reverse—the build-up of a protein associated with Parkinson’s.

The study, published in Cell Reports, supports the idea of a link between brain function and the gut microbiota. “The results provide an opportunity to investigate how changing the bacteria that make up our gut microbiome affects Parkinson’s,” says study senior author Maria Doitsidou, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom.

The new study builds up on previous research that has linked changes in the gut microbiota composition with the development of Parkinson’s disease. But how gut bacteria affect this neurodegenerative disorder remains unclear.

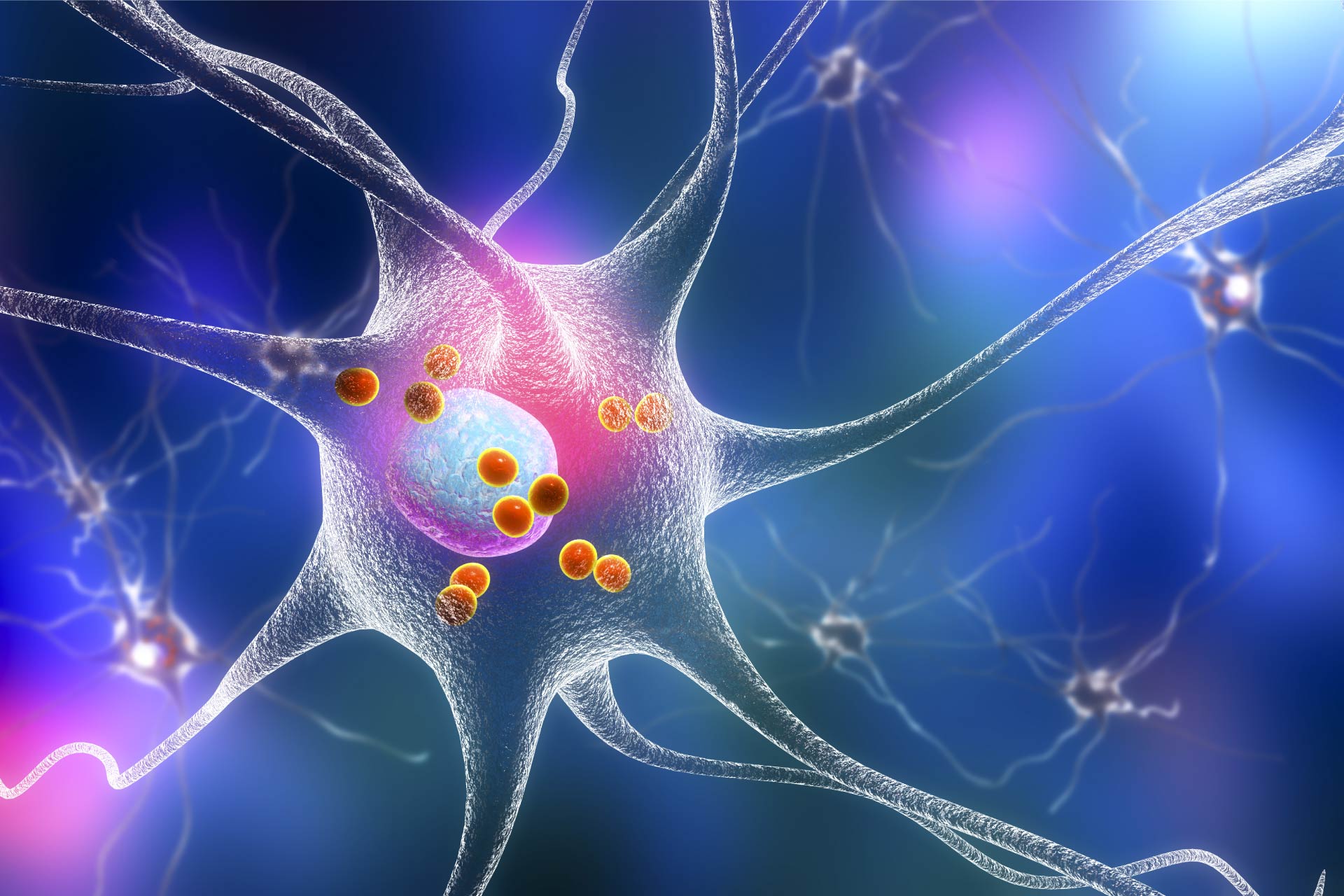

In the brains of people with Parkinson’s, a protein called alpha-synuclein misfolds and then clumps together into structures that are toxic to the nerve cells responsible for producing the neurotransmitter dopamine. The death of these cells causes the symptoms associated with Parkinson’s, which include tremors and slowness of movement. At the moment, there is no treatment that can slow, reverse, or protect people with Parkinson’s from disease progression.

To find out whether changes in the gut microbiota composition could affect alpha-synuclein build-up, Doitsidou and her team studied C. elegans roundworms that had been genetically engineered to produce the human version of alpha-synuclein.

Protective bacteria

The researchers fed the worms various commercially available probiotics. Worms that were given a specific strain of Bacillus subtilis, called PXN21, had fewer alpha-synuclein clumps in their nerve cells than worms raised on other probiotics. B. subtilis not only had a protective effect against the build-up of alpha-synuclein, it also cleared away some of the protein clumps that had already formed in older worms.

What’s more, B. subtilis improved the movement defects associated with alpha-synuclein clumps, and these beneficial effects lasted for the worms’ entire lifespan.

Fat metabolism

The researchers found that B. subtilis bacteria were able to prevent the formation of toxic alpha-synuclein clumps by changing how the worms processed fats called sphingolipids. Previous studies have suggested that sphingolipid metabolism can contribute to the development and progression of Parkinson’s disease. “We propose that alterations in sphingolipid metabolism triggered by the B. subtilis diet result in a reduction of alpha-synuclein aggregation in C. elegans,” the researchers say.

While encouraging, the findings are preliminary and must be confirmed in mice, a model organism much more closely related to people than worms, Doitsidou says. If successful, the tests in mice will be followed by fast-tracked clinical trials, since B. subtilis is already available as an over-the-counter probiotic, she says.

“The results from this study are exciting as they show a link between bacteria in the gut and the protein at the heart of Parkinson’s,” says Beckie Port, research manager at a London-based Parkinson’s research charity, which funded the study. “Studies that identify bacteria that are beneficial in Parkinson’s have the potential to not only improve symptoms but could even protect people from developing the condition in the first place,” Port says.