• Gut metabolites

• Microbial shifts

What is already known on this topic

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) have been associated with changes in the gut microbiota composition and the levels of certain host and microbial metabolites in the digestive tract. But how specific metabolites affect gut bacteria remains unclear.What this research adds

Researchers found that a class of signaling lipids stimulated growth of bacterial species that are typically over-represented in people with IBD. The levels of these lipids were elevated in the stool of IBD patients and in a mouse model of chronic inflammation of the inner lining of the colon.Conclusion

The findings could inspire the development of therapies that target specific classes of metabolites to prevent deleterious changes in the gut microbiota composition.

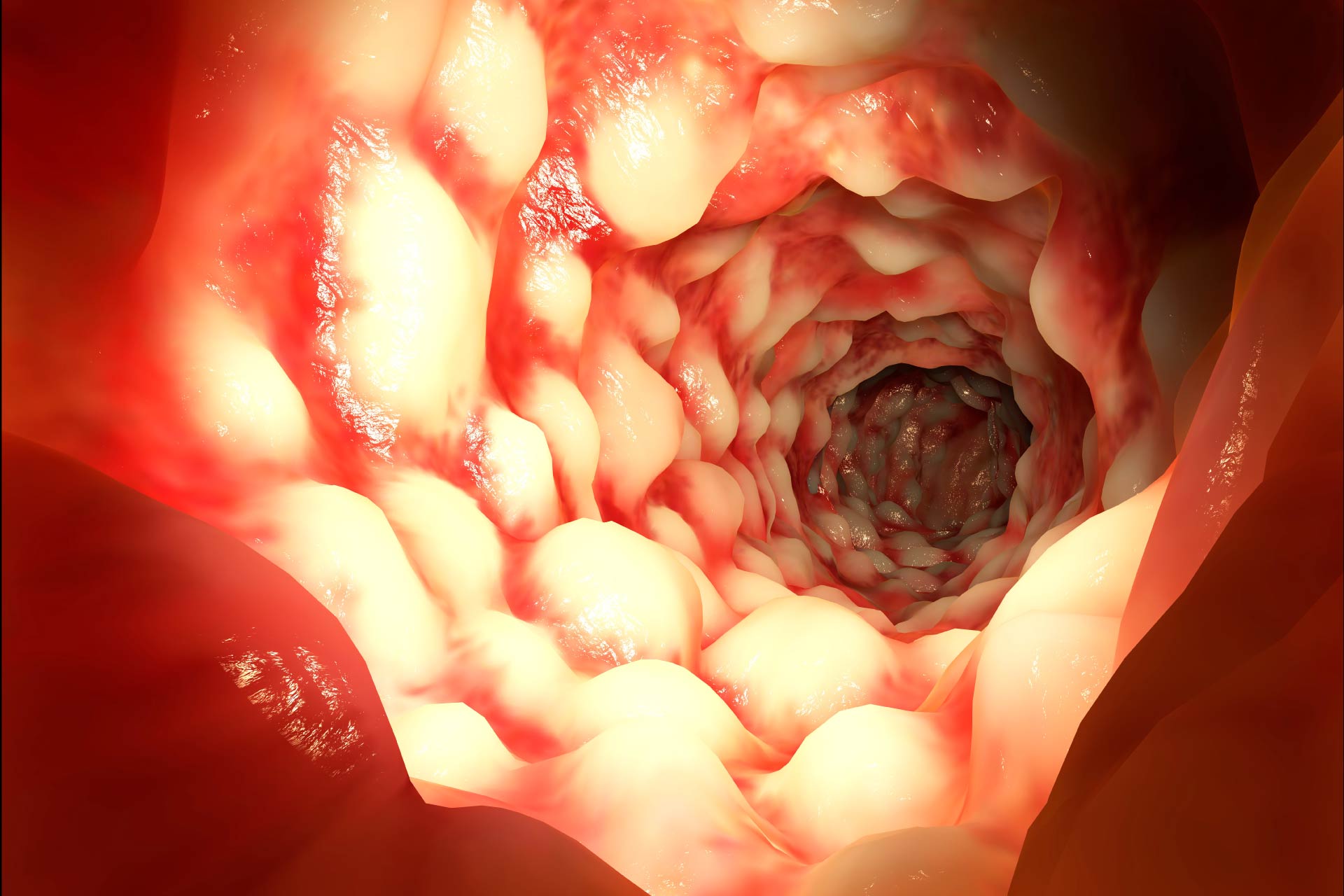

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), a group of intestinal disorders that cause prolonged inflammation of the digestive tract, have been associated with changes in the gut microbiota composition. Now researchers have found a class of metabolites that can shift the gut microbiota towards an IBD-like composition.

The findings, published in Nature Microbiology, could inspire the development of therapies that target specific metabolites to prevent deleterious changes in the gut microbiota makeup, the researchers say.

“Inflammatory bowel diseases, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, are conditions of chronic gastrointestinal inflammation resulting from genetic predisposition and perturbed interactions between gut microorganisms and host immunity,” the researchers say. Although the levels of certain human and microbial metabolites in the digestive tract have been linked to IBD, how specific metabolites affect gut bacteria remains unclear.

Nadine Fornelos at the Broad Institute and her colleagues studied how gut metabolites that are abundant in IBD patients affect the growth of gut bacteria that have been associated with the disease.

Gut metabolites

The researchers found that a class of signaling lipids called N-acylethanolamines were enriched in stool from IBD patients and in a mouse model of chronic inflammation of the inner lining of the colon. N-acylethanolamines are produced by the host and are involved in several biological processes, including inflammation and gut barrier function, the team says.

In the laboratory, N-acylethanolamines inhibited the growth of Bacteroides cellulosilyticus and increased that of Escherichia coli, Ruminococcus gnavus and Blauta producta. All these bacteria are known to be altered in people with IBD. N-acylethanolamines, the researchers concluded, “enhance growth of species enriched in IBD and inhibit growth of species depleted in IBD.”

Microbial shifts

The team also found that N-acylethanolamines can shift the gut microbiota from a healthy to an IBD-like composition in bacterial communities grown in the laboratory, with Proteobacteria blooming and Bacteroidetes declining. For example, microbes such as B. producta, Clostridium clostridioforme and Klebsiella pneumoniae, which are over-represented in people with IBD, increased in the presence of N-acylethanolamines.

“Perhaps the most compelling response to N-acylethanolamines was Enterobacteriaceae expansion, a hallmark of IBD,” the researchers say. Enterobacteriaceae can trigger the production of lipopolysaccharide, a large molecule that activates inflammatory responses and is important in the development of IBD. High levels of specific N-acylethanolamines also increases gut permeability, which contributes to inflammation, the team adds.

Although it remains unknown how N-acylethanolamines change the gut microbiota composition, the findings suggest that these molecules can be used as a biomarker for diagnosing IBD, the researchers say.