• Microbial biomarkers

• Shaping the microbiota

• Modulating microbial metabolism

What is already known on this topic

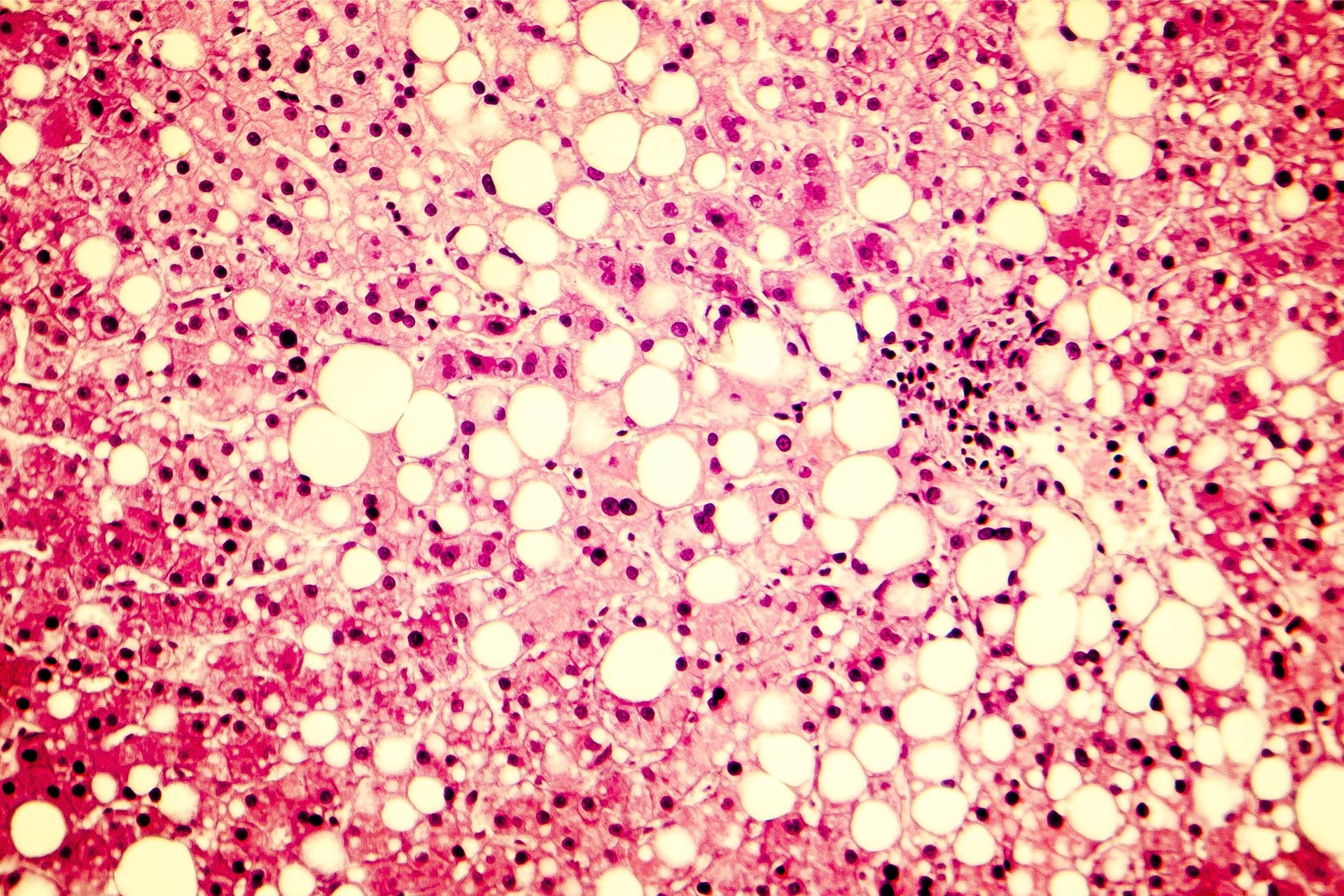

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a metabolic condition characterized by an excessive build-up of fat in the liver of people who drink little or no alcohol. The condition, which is usually seen in overweight or obese individuals, is a major risk factor for liver cancer. Increasing evidence suggests a link between the gut microbiota and the development of NAFLD.What this research adds

Researchers have highlighted how the current knowledge of the gut-liver axis in NAFLD may lead to the development of microbiota-based personalized approaches for managing the condition. Gut microbes could be employed as a biomarker for NAFLD diagnosis, as a target for therapeutic interventions, and as a marker of responses to treatment.Conclusion

Understanding the interactions between the microbiota and its host in NAFLD could help to prevent and treat the condition.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a metabolic condition characterized by an excessive build-up of fat in the liver of people who drink little or no alcohol. The condition, which is usually seen in overweight or obese individuals, is a major risk factor for liver cancer. Increasing evidence suggests a link between the gut microbiota and the development of NAFLD—a finding that could open the door to the development of gut microbiota-based personalized approaches to prevent and treat the condition.

Rohit Loomba at the University of California, San Diego, and his colleagues have highlighted how the current knowledge of the gut-liver axis in NAFLD may lead to the development of microbiota-based personalized approaches for managing the condition.

“The prospect of incorporating the gut microbiome in the management of NAFLD, among other metabolic co-morbidities associated with it, such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, offers an exciting and novel strategy for disease prevention and/or management,” the researchers say.

Microbial biomarkers

The traditional way to diagnose NAFLD is through a liver biopsy—an invasive procedure that carries risks including bleeding, collapsing of the lungs, and even death. Several studies have revealed an association between alterations in the gut microbiota composition and NAFLD severity, particularly in people with NAFLD-related advanced fibrosis, which is the scarring of the liver. Advanced fibrosis is associated with an overall decrease in microbial diversity and an increase in Bacteroides and Escherichia species.

“These results suggest that there is the potential for a fecal sample to yield a non-invasive assessment of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD, perhaps negating the need for more invasive assessments such as liver biopsy,” the researchers say.

However, they add, there are some limitations in the use of the gut microbiota as a biomarker for NAFLD diagnosis. A number of factors — including age, sex, and lifestyle — can shape the gut microbiota composition. What’s more, there may not be just one microbial fingerprint of disease in NAFLD; indeed, researchers have found an overlap of microbiota signatures among different conditions. Finally, the gut microbiota can be characterized using a variety of methods, which may reduce the reproducibility of results across studies.

Shaping the microbiota

At the moment, there’s no established FDA-approved pharmacologic therapy for NAFLD. “The prospect of manipulating the gut microbiome in the management of NAFLD offers an exciting and novel strategy for disease prevention and/or management,” the researchers say. “However, establishing causality in microbiome-host interactions remains a challenge.”

Recent studies have shown that the gut microbiota can influence the migration, function, and differentiation of several populations of immune cells. This suggest that targeting microbial-associated recruitment of some of these immune cells to the gut and liver could potentially be used as a therapy for NAFLD.

The most common strategies to alter the microbiota composition include the use of antimicrobials, living microorganisms such as probiotics, and prebiotics—indigestible dietary fibers that stimulate the growth of microbes. A recent analysis of 21 clinical trials showed that the use of probiotics was associated with improvement in specific markers of liver inflammation.

Another approach to modulate the microbiota is through fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), which is widely used to treat people with bowel infections caused by the bacterium Clostridioides difficile who had failed to respond to other treatments. So far, FMT trials have been done on obese individuals with metabolic syndrome but without a clear diagnosis of NAFLD. The researchers caution that FMT can be associated with risks for the recipient, including the transplantation of pathogenic microbes.

Using bacteriophages — viruses that only infect bacteria — has also been explored as a way to modulate the microbiota, and the approach has shown promise in a mouse model of alcoholic hepatitis. “However, phage therapy to target the gut microbiota in liver disease has not been studied outside of murine models and requires further evaluation not only for efficacy but also for clinical safety in humans,” the researchers say.

Modulating microbial metabolism

There’s mounting evidence that the gut microbiota contributes to disease through the action of metabolites, which are bioactive compounds synthesized from the microbial metabolism of food or host-derived molecules such as bile acids. Ways to modulate microbial metabolism include administering molecules that inhibit certain bacterial enzymes or genetically engineering bacteria to perform specific functions.

Two recent studies uncovered microbial-derived small molecules that could have implications in the treatment of NAFLD, but the molecules have not yet been studied in people. A third study showed that deleting a single bacterial gene from a Bacteroides strain modulated the bile acid pool of living mice, leading to weight gain and increased lipid levels—a finding that suggests a link between the gut microbiota and bile acid metabolism in metabolic disease.

Since diet is an important contributor in the development of NAFLD, and because diet-microbiota interactions may affect the progression of metabolic diseases, optimizing nutrition should be a priority in the management of NAFLD.

Several studies have revealed an association between sugar consumption and NAFLD, and diets rich in animal or plant proteins have been shown to decrease liver inflammation in people with NAFLD. Although a ‘one size fits all’ strategy for the management of metabolic disease may be inadequate, “there is mounting evidence for the potential for personalized dietary approaches,” the researchers say.

Finally, a number of studies have shown that individual responses to drugs vary depending on the composition of the gut microbiota. But whether the gut microbiota could serve as a marker for individuals’ response to NAFLD drugs is unclear, the researchers say. “A broader understanding of microbial metabolism may lead to personalized drug selection,” they say.