-

What is already known on this topic

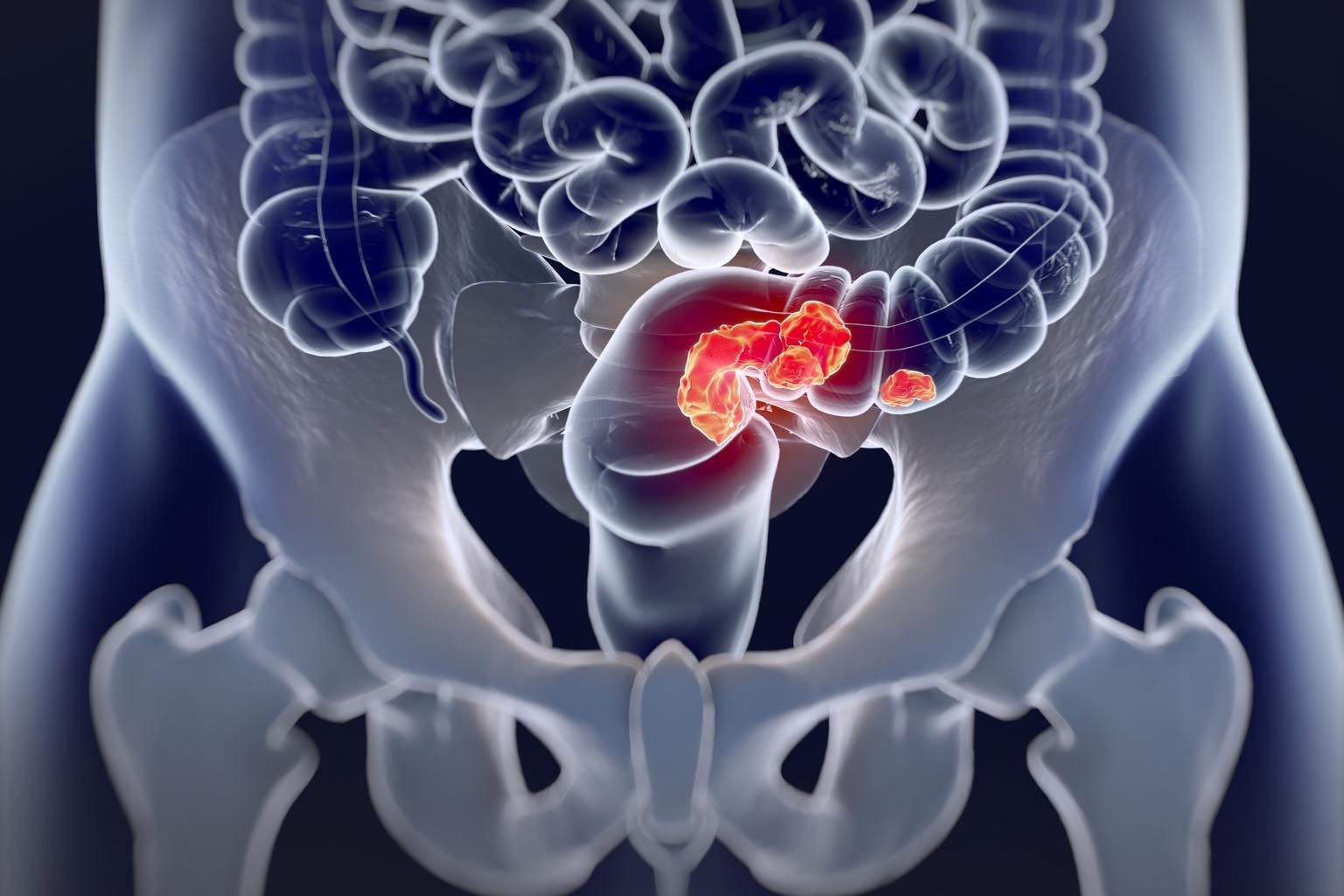

Microbes are thought to be crucial for the development of several types of cancer, but the role that gut-dwelling bacteria play in colorectal cancer – one of the most common and deadly cancers – is poorly understood. -

What this research adds

By combining data from several existing microbiome association studies of colorectal cancer with newly generated data, researchers have found changes in gut microbiota composition that associate with colorectal cancer and are consistent across different countries, diets, and lifestyles. -

Conclusions

The study identifies microbial biomarkers of colorectal cancer and paves the way for the development of non-invasive, microbial-based predictive tests.

Gut microbes have been linked to several conditions – from depression to obesity – but the role that gut-dwelling bacteria play in colorectal cancer – one of the most common and deadly cancers – is poorly understood. Now, researchers have found that specific changes in gut microbiota composition are associated with colorectal cancer.

The study, led by Andrew Maltez Thomas at the University of Trento, also shows that disease-specific changes in the microbiota make-up do not depend on the dietary habits of the populations studied and are consistent across countries and lifestyles. The results were published in Nature Medicine.

Several studies have looked at the association between https://microbiomepost.com/how-a-gut-microbe-may-suppress-colorectal-cancer-growth/specific gut microbes and colorectal cancer, but how accurate and reproducible these microbial signatures are across different populations remains unclear. So the researchers combined data from all existing microbiome association studies with data from 140 new samples. Then, they assessed how accurately the gut microbiota could predict colorectal cancer across populations.

Cancer signatures

In total, the team analyzed samples from 969 individuals in Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, and the United States: 413 samples came from people with colorectal cancer, 143 from individuals with a benign colorectal tumor, and 413 from healthy people samples.

Compared to the gut of healthy people, that of individuals with colorectal cancer had more bacteria, especially those deriving from the mouth, which may be a sign of an altered gut microbiota.

In particular, people with colorectal cancer had increased levels of Fusobacterium nucleatum, which is known to cause colorectal cancer in mice, Solobacterium moorei, Porphyromonas asaccharolytica, Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, and bacteria belonging to the Parvimonas family.

Instead, healthy individuals showed a high abundance of Gordonibacter pamelae and Bifidobacterium catenulatum, which are considered beneficial microbes and have been used as probiotic supplements.

When the researchers looked at the functions of the bacteria associated with colorectal cancer, they found an overrepresentation of the biological pathways for the generation of glucose and the ability to metabolize amino acids. These included pathways responsible for turning different amino acids into tumor-promoting compounds such as polyamines. Pathways for the degradation of starch and other sugars such as galactose were instead associated to the bacteria dwelling in the gut of healthy individuals.

What’s more, the team also found an association between colorectal cancer and the presence of the gene for a microbial enzyme that degrades choline, a nutrient that is abundant in diets containing large amounts of red meat and other fatty foods. This finding supports the idea that a diet rich in fat could contribute to cancer development.

Although the findings do not show that alterations in gut microbiota composition cause colorectal cancer, the study identifies microbial biomarkers of colorectal cancer, opening the way for the development of non-invasive, microbial-based predictive tests.