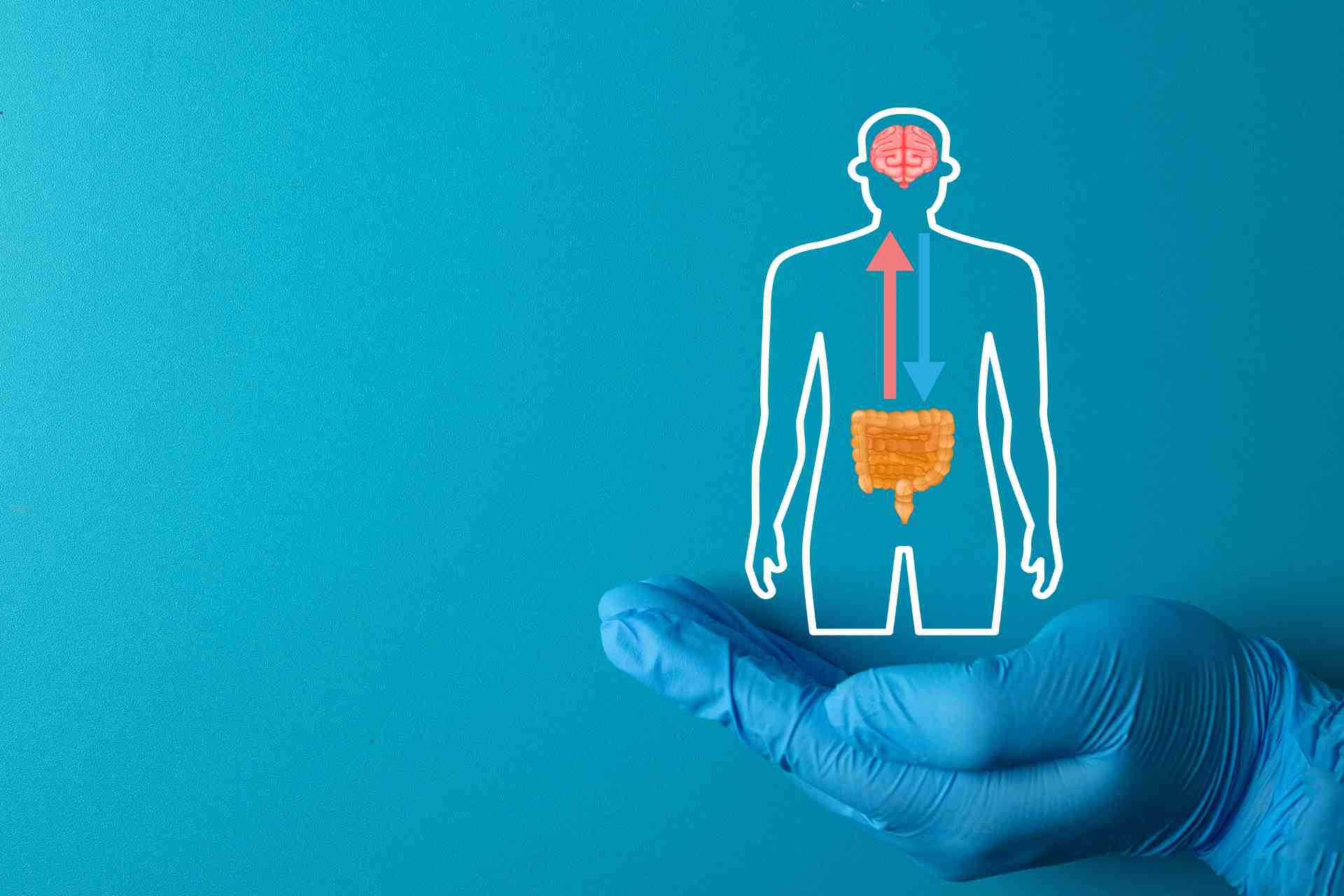

The gut-brain axis—a communication network connecting the digestive and nervous systems—has recently emerged as a key factor in neurodegeneration. Now, an analysis of hundreds of thousands of participants across several biobanks found that conditions affecting the gut-brain axis play an important role in the risk of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

The findings, published in Science Advances, indicate that combining data about gut-brain–related disorders with genetic and other information provides a powerful approach for predicting these neurodegenerative diseases.

Recent studies suggest that disorders of the gut-brain axis influence the risk of developing Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. However, more work is needed to understand the connection between disorders of the gut-brain axis and neurodegeneration.

Mohammad Shafieinouri at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and his colleagues set out to look for patterns linking gut-brain–related disorders, genetics, and blood-based biomarkers to the risk of developing Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

To do so, they analyzed data from more than 500,000 participants across three large biobanks: the UK Biobank, the Secure Anonymized Information Linkage databank, and FinnGen. These biobanks collect and link large-scale health, genetic, and clinical data from hundreds of thousands of participants.

Gut-brain axis

The researchers identified specific conditions within the gut-brain axis that are linked to increased risk for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. For Alzheimer’s, disorders including gastritis, gastroenteritis and colitis were associated with higher hazard ratios years before diagnosis. For Parkinson’s, associations were observed for functional intestinal disorders, pancreatic internal secretion disorders, and deficiencies in B group vitamins.

These findings were robust across multiple datasets and time intervals, demonstrating that risk can be elevated up to 15 years before diagnosis. Genetic analyses revealed that people with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease who also had co-occurring gut-brain axis–related conditions often had less genetic risk for the disease compared to those who developed Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s without such conditions.

This suggests that non-genetic factors, including metabolic and digestive disorders, may play a role in disease development, the researchers say.

Predicting disease

Further analyses supported the relevance of the gut-brain axis in neurodegeneration. Specific blood-based biomarkers were increased in people with Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease, reflecting underlying neuronal damage. Other proteins showed altered levels in people with co-occurring metabolic or digestive conditions.

By combining clinical, genetic and other types of data into models, the researchers could predict who was more likely to develop Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. Age and molecular biomarkers were the strongest predictors of these neurodegenerative diseases, while traditional clinical features contributed relatively little, the team found.

“This endeavor illuminates the interplay between factors involved in the gut-brain axis and the development of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, opening avenues for therapeutic

targeting and early diagnosis,” the authors say.