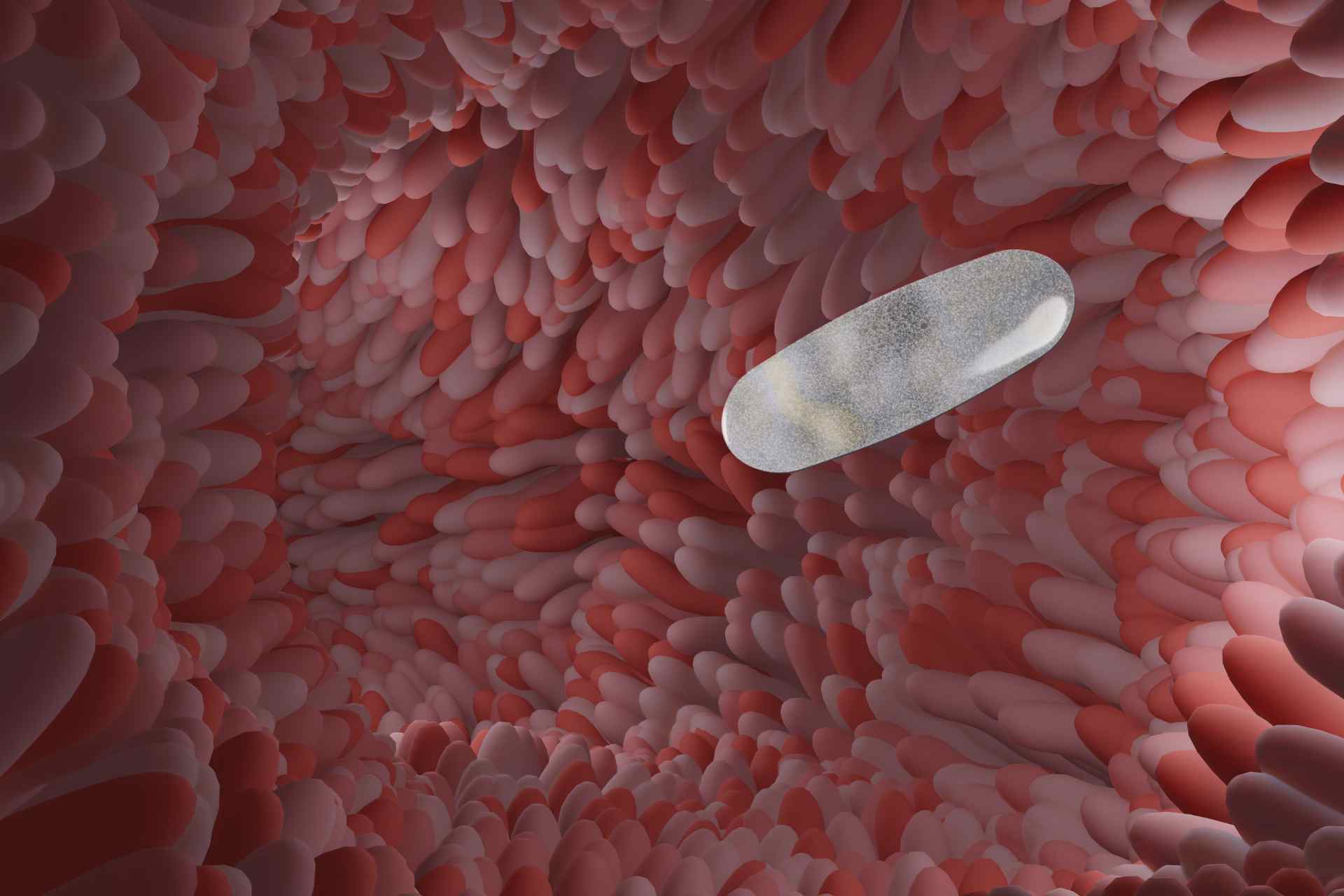

Although different regions of the gut host distinct microbial communities, current methods for studying them are limited: stool samples fail to capture the upper gut microbes, and endoscopy is accurate but invasive. Now, researchers have developed an ingestible capsule—called CORAL—to sample microbial communities from the small intestine, which are typically underrepresented in stool samples.

The findings, published in Device, show that CORAL can sample the microbes residing in upper gut in a non-invasive and reliable way, offering a tool for studying the diversity of the microbiota.

“Fecal sampling alone overlooks substantial microbial diversity, particularly in the proximal gut,” the authors say. Capsule-based technologies have emerged as a minimally invasive way to study gut microbes, but more reliable methods are needed to better understand the microbiota.

So, researchers led by Hanan Mohammed at New York University Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates set out to design a capsule made of a porous lattice inspired by coral.

Coral-inspired capsule

To figure out the best structure for trapping gut bacteria, the team used computer simulations to test how fluids—and the bacteria in them—would flow through different types of lattice. They found that a specific lattice with a twisting, tortuous path was better at capturing bacteria than a simpler straight design.

By adjusting pore size and other characteristics of the lattice, the researchers created a capsule that lets gut fluids flow in easily, while preventing bacteria from leaking out. The capsule—dubbed CORAL—is 8 millimeter long and 2 millimeter wide, and it is manufactured in a single step using 3D printing.

The CORAL capsule is made of three parts: a shell, an internal core, and a cap. These parts together allow it to collect gut bacteria from the small intestine without contamination from other parts of the digestive tract.

Spatial complexity

In rat models, the core of the CORAL capsule captured microbial communities from the small intestine, including mucosa-associated bacteria, which are typically under-represented in stool samples. Its outer shell captured fecal microbiota instead.

CORAL capsules were given to the rats orally inside a protective gelatin shell that prevented release in the stomach. The capsules moved smoothly through the gut and were later retrieved without signs of aggregation.

CORAL capsules were well-tolerated and caused no gut damage, demonstrating their potential as a safe, noninvasive tool for studying the human gut microbiota, the authors say. “A richer understanding of the upper [gastrointestinal] microbiome is crucial for capturing baseline microbial ecology and for identifying their associations with diet, lifestyle, health, disease, and aging.”