The gut immune system is shaped not only by the microbiota but also by what we eat, including nutrients and contaminants such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS)—large molecules found on the outer membrane of some bacteria. Now, researchers have found that dietary components—especially LPS—can influence the development and diversity of the gut’s immune response, even without any microbes present.

The findings, published in Immunity, show that dietary LPS can mimic microbial signals and drive gut immune development, with early-life being a critical window for shaping gut immunity independently of the microbiota.

Scientists have known that the gut’s immune system interacts with a mix of microbes and dietary components. For example, fiber from food is broken down by gut bacteria into short-chain fatty acids that support immune health. Some food contaminants, including LPS, can also trigger immune responses. But whether diet alone can shape gut immunity, especially during early development, remains unclear.

Catherine Mooser at the University of Bern in Switzerland and her colleagues studied how different diets affect the immune system of mice, focusing on a specific type of antibody called IgA, which helps protect the gut.

Food contaminants

The researchers raised germ-free mice on either a high-fat diet, a high-starch diet, or a more complex grain-based chow, all under sterile conditions to study the effects of diet alone, without influence from bacteria.

Mice fed the simpler diets had fewer and less diverse IgA antibodies compared to those raised on the more complex chow. However, this effect only occurred when the diet was given from birth—switching diets in adulthood did not have the same impact.

The chow-fed mice, which contains natural contaminants such as LPS, also had more active immune cells in their gut than mice on purified diets. Mice genetically unable to respond to LPS had fewer immune cells regardless of the diet they were fed, confirming that LPS in the chow helps drive immune responses in the gut.

Shaping responses

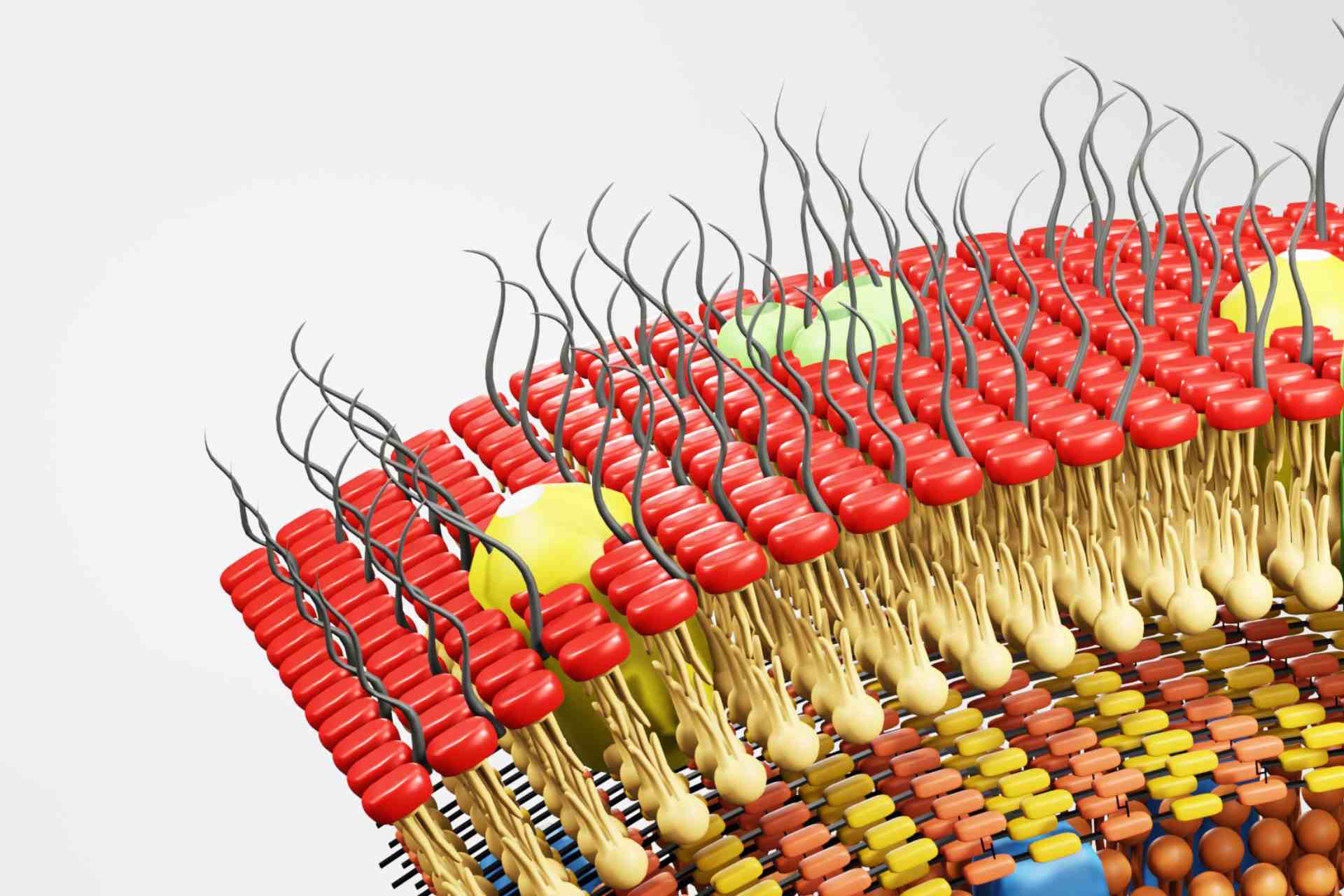

Adding LPS to a purified diet wasn’t enough to restore normal gut immune activity in mice, but when LPS and a protein were delivered together inside tiny fat-based particles called liposomes, the mice’s gut immune system responded strongly, producing more immune cells and antibodies.

These results show that dietary LPS, especially when absorbed in lipid-based particles, can mimic microbial signals and drive mucosal immune development, the researchers say.

The findings also highlight how diet, especially LPS in the right form, shapes gut immune responses and may inform future approaches in food and medicine. “These observations are relevant to the debate on reintroduction of safe microbes into industrialized food and the use of microbial systems of pharmaceutical delivery,” the authors say.