What is already known on this topic

The human skin is home to a diverse community of microbes, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Changes in the composition of the skin microbiota have been associated with conditions such as acne and atopic dermatitis. However, the exact makeup of the skin microbiota remains unclear.

What this research adds

Researchers sequenced the genetic material of microbes present in nearly 600 samples collected from the skin of 12 healthy people. Using these data, they created the Skin Microbial Genome Collection (SMGC) — a collection of reference genomes that includes 174 previously unknown bacterial species, four new eukaryotes and 20 jumbo phages — very big viruses that infect bacteria — that inhabit the human skin.

Conclusions

The SMGC allows researchers to classify about 85% of genetic sequences from the skin microbiota; it also offers valuable insights into skin microbiota diversity.

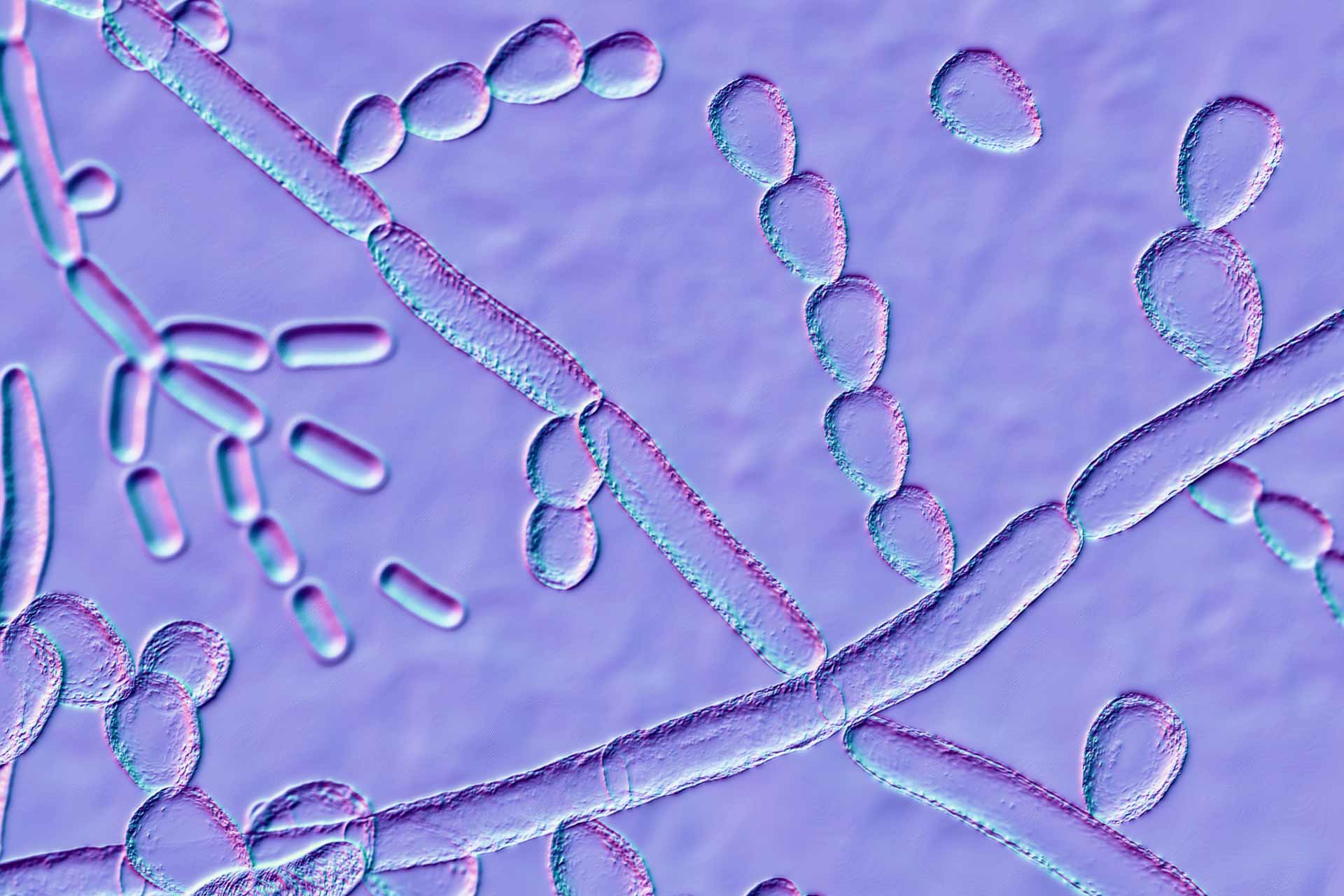

The human skin is home to a diverse community of microbes, including bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Now, researchers have identified new members of the skin microbiota and created a collection of their reference genomes.

The collection, called Skin Microbial Genome Collection (SMGC), allows researchers to classify about 85% of genetic sequences from the skin microbiota; it also offers valuable insights into skin microbiota diversity. The study was published in Nature Microbiology.

“This work is a major step toward obtaining a complete genomic blueprint of the skin microbiome,” says study co-senior author Julie Segre at the National Institutes of Health. “We hope these data will support future investigations improving our understanding of skin health and disease.”

Several studies have showed that changes in the composition of the skin microbiota are associated with conditions such as acne and atopic dermatitis. However, the exact makeup of the skin microbiota remains unclear.

To work out the diversity of skin microbes, Segre and her colleagues analyzed the genetic material of bacteria, viruses, and eukaryotes present in 594 samples collected from the skin of 12 healthy people. The samples were taken at three time points from 19 body sites of the study participants.

Microbial collection

The researchers combined lab culturing methods with metagenomic sequencing to investigate the diversity of the skin microbiota to assemble the Skin Microbial Genome Collection (SMGC), which comprises 622 prokaryotic species that inhabit the human skin.

The researchers also found 174 previously unknown bacterial species — including ‘Candidatus Pellibacterium’, which had not been associated with the skin before — as well as 20 jumbo phages.

Three to five times larger than an average virus, jumbo phages infect only bacteria and were found most commonly on the hands and feet of study participants. “These areas of the body have highly diverse microbiomes, which makes sense because we’re constantly using our hands to touch new things in our environment,” says study first author Sara Kashaf. “Our future work will aim to understand what these different microbes are doing within these communities,” she says.

New fungi

In addition to bacteria and viruses, the researchers also discovered 12 genomes from fungi, four of which had not been identified before. “Some of these genomes were already known, such as Malassezia globosa, which has been associated with the healthy skin mycobiome but has also been associated with conditions such as dandruff,” says study co-author Rob Finn at EMBL-EBI. “Using the same methods that recovered eight known genomes gives us confidence in the four novel eukaryotes that we found,” he says.

The researchers found that the Actinobacteriota phylum is the most common on the skin, representing 38% of the species in the SMGC. The genus Corynebacterium contained the greatest number of newly identified skin species. Nearly 50 species were shared by all twelve 12 study participants, and Cutibacterium acnes and Lawsonella clevelandensis A were the most abundant bacteria on the skin.

The study focused mostly on people from the United States, but future work should expand the SMGC by looking at the skin microbiota of different populations, the authors say.