What is already known

Most colorectal cancers start as non-cancerous growths called polyps, which can be of two types. A sizeable portion of these pre-cancerous lesions are caused by environmental factors such as smoking or being overweight, and the gut microbiota has been proposed as an integrator of such environmental risks. But it’s unclear whether there are microbiota signatures associated with each of the two types of polyps that precede colorectal cancer.

What this research adds

Researchers analyzed stool samples from 971 people undergoing colonoscopy as well as the individuals’ dietary information and medication history. One type of polyps called serrated adenomas associated with short-chain fatty-acid-producing microbes such as Ruminococcus lactaris, Eubacterium ventriosum and Alistipes shahii. Microbial species that were abundant in people with another type of polyps called tubular adenomas included Bacteroides stercoris, Flavonifractor plautii and Roseburia intestinalis. The researchers also found links between environmental factors, including diet, and most of the identified microbial species. In particular, Flavonifractor plautii was associated with the degradation of beneficial anti-cancer molecules.

Conclusions

By providing insights into how the gut microbiota influences cancer susceptibility, the findings may help to develop new therapies or dietary interventions.

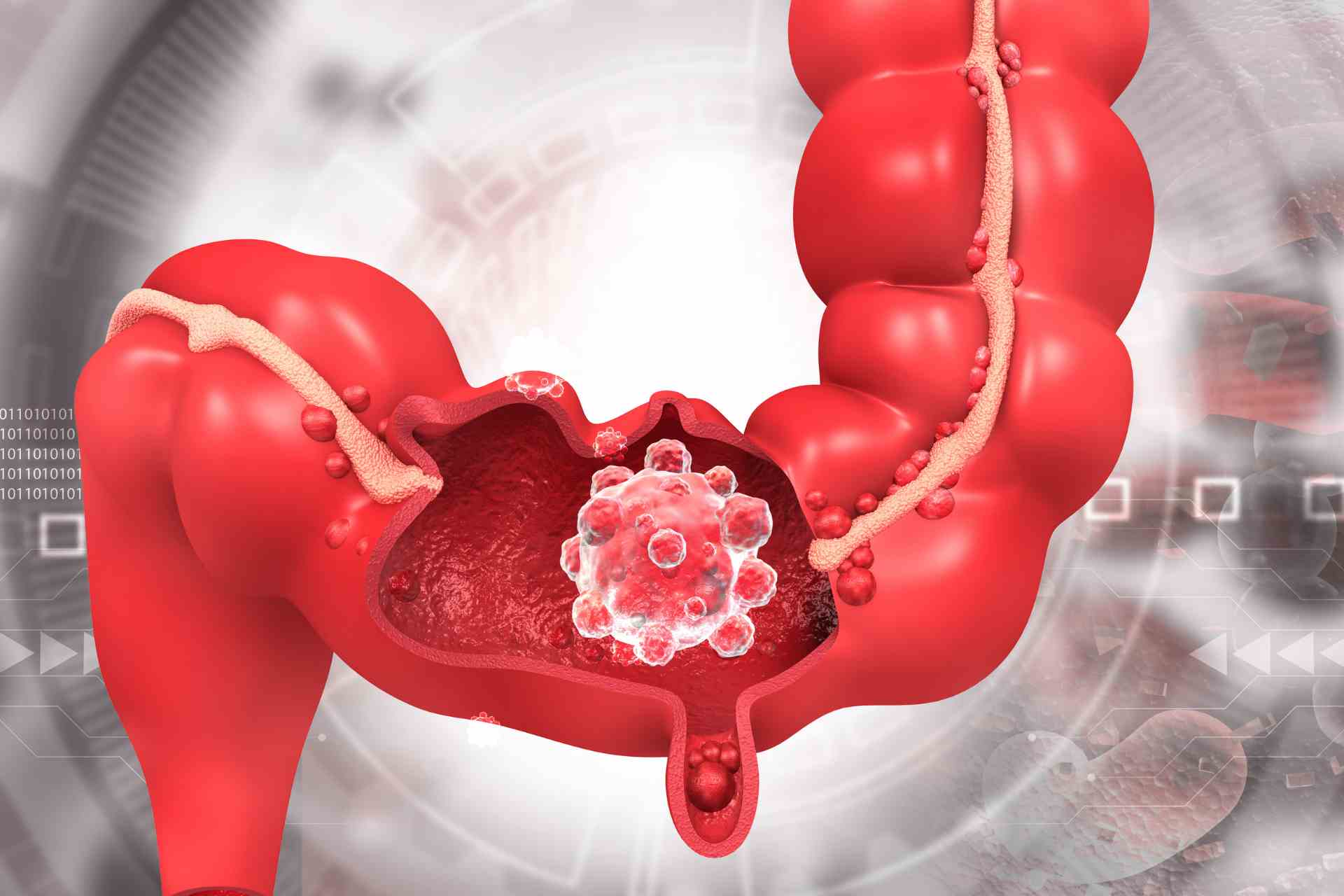

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the world. Now, researchers have found distinct microbial signatures that associate with the most common types of pre-cancerous lesions.

The findings, published in Cell Host & Microbe, provide insights into how the gut microbiota influences cancer susceptibility. “The unique dependencies of each premalignant lesion may be exploited therapeutically or through dietary intervention,” the researchers say.

Most colorectal cancers start as non-cancerous growths called polyps, which can be of two types: serrated adenomas, which have a saw-tooth appearance under the microscope, and the more common tubular adenomas, which show a tubular growth pattern. A sizeable portion of these pre-cancerous lesions are caused by environmental factors such as smoking or being overweight, and the gut microbiota has been proposed as an integrator of such environmental risks. But it’s unclear whether there are microbiota signatures associated with each of the two types of polyps that precede colorectal cancer.

To assess whether — and how — the interplay between the microbiota and environmental risk factors differs between serrated and tubular adenomas, researchers led by Jonathan Wei Jie Lee at the National University of Singapore analyzed stool samples from 971 people undergoing colonoscopy as well as the individuals’ dietary information and medication history.

Microbial fingerprint

About 550 study participants were adenoma-free, 321 had tubular adenomas, 62 had serrated adenomas, and 36 had both serrated and tubular adenomas. Compared with controls, people with tubular adenomas tended to be older and take more aspirin, and those with either tubular or serrated adenomas had a lower dietary intake of vegetables.

The four environmental factors with the greatest effect on microbiota differences were age, sex, body mass index and the presence of either tubular or serrated adenomas. Fiber-rich foods such as fruits and vegetables, red and processed meats and common medications also had significant effects on microbiota differences, the researchers found.

Microbial species that were abundant in people with serrated adenomas included short-chain fatty-acid-producing microbes such as Ruminococcus lactaris, Eubacterium ventriosum, Odoribacter splanchnicus, Anaerostipes hadrus and Alistipes shahii, whereas Flavonifractor plautii, Bilophila wadsworthia, Bacteroides stercoris, Clostridium asparagiforme, Clostridium bolteae CAG 59 and Roseburia intestinalis were more common in people with tubular adenomas.

Environmental links

An analysis of the gene families linked to the gut microbiotas of each group of people revealed that serrated adenomas tend to associate with multiple microbial antioxidant defense systems. Tubular adenomas, instead, were linked to a reduction in a process called methanogenesis — the final step in the decay of organic matter, and the metabolism of mevalonate, a component of a pathway providing metabolites for multiple cellular processes.

The researchers also found links between environmental factors, including diet, and most of the identified microbial species. Flavonifractor plautii and Bacteroides stercoris, for example, were more abundant in people with tubular adenomas than in those with serrated adenomas or in controls. Both microbes were also less abundant in people with an increased vegetable intake or those who took aspirin.

“The plausible role of Flavonifractor plautii appears to be linked to the degradation of beneficial anticarcinogenic flavonoids,” the researchers say. “We hypothesized that beneficial impact of increased vegetable consumption and aspirin use on lowering risk of [tubular adenomas] and [serrated adenomas], respectively, could be mediated by negating the effects of Flavonifractor plautii.”