Much anticipated changes to the taxonomy of the Lactobacillus genus were finally published recently … but what to the changes mean for industry activities? Who will be affected, and what will you have to change?

In the simplest essence, the publication of updated taxonomy for Lactobacillus means that almost all bacteria that were previously grouped and named under the Lactobacillus genus will now have a new (albeit quite similar) name.

From more than 250 species that were previously classed in the Lactobacillus genus only 35 remain – including Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus helveticus. This means the names of more than 200 bacterial strains have changed – with popular strains including Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus reuteri, and Lactobacillus rhamnosus all assigned new names.

Why change?

The update to taxonomy is several years in the making. The Lactobacillus category was established in 1901, but in the last century many new strains have ben added to the group – meaning that the grouping became very large and contained many different strains that were sometimes quite unrelated.

Writing in a blog for the International Probiotic Association, Bruno Pot of Yakult Europe and Vrije University, noted that in the past specific properties like the shape and size (length, diameter), colour when grown in the lab, and chemical reactions they can perform (for example to ferment and produce yoghurt) have been used to group bacteria into species.

“This turned out to be very practical, but not always very correct,” he said. “Nowadays scientists can use the genetic information of bacteria (their complete genome actually) to compare them and to decide if they belong to the same genus and species, or not.”

“When this was done on all 255 Lactobacillus species, it turned out that huge mistakes were made in the past. Mistakes that would have put humans in the same species as cats, dogs, even as frogs.”

Indeed, it was back in 2012 that a group of Italian researchers first published a paper that analyzed the genetics of the strains of bacteria grouped Lactobacillus genus. It found that the species that were too different from each other genetically, and suggested that the large group was divided up into new smaller groups that helped scientists to be more accurate and organised.

For the last eight years researchers have been working to devise a new way to categorise the strains that is both accurate but also has as little impact as possible on industry and consumers.

“This task had been on the agenda of scientists for a while,” says study co-author Dr Sarah Lebeer from the University of Antwerp, Belgium.

“We are pleased that we managed to unite different international teams working on comparative genomics of Lactobacillus with taxonomy experts, collaborating for the best interest of the whole field.”

According to the naming conventions for all living things, the first species ever described as a Lactobacillus gets to retain its genus name – so the yogurt-making bacterial species Lactobacillus delbruecki will keep its name, along with bacteria that are closely related to it.

“I admit it’s a bit painful to see the names of my favourite bacteria change,” adds Lebeer, who is a board member for the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP). “Yet I look forward to the new insights provided by this comprehensive analysis of taxonomy, evolutionary history, physiology, and ecology of lactobacilli. “

“The most closely related bacteria sharing most properties now have the same genus name, while lactobacilli that are more distantly related can be more clearly discriminated from each other.”

What are the implications?

Moving forward, the new names of strains will have to be used on all product labels, plus all scientific, legal and technical documentation including internal QA paperwork, plus and other communications to consumers, the scientific community and medical professionals.

Nina Vinot of Probiotical told Microbiome Post that the potential impacts on industry are large, since this means that product packaging, websites, and other consumer-facing information, in addition to internal documents will need to be checked and updated.

She added that in some cases the names of strains on labels will also take up more space, which may have implications for product packaging.

According to a recently published paper led by Bruno Pot, the changes will impact the consumer, the scientific and medical or veterinary communities, regulators, governments, lawyers and companies.

“Consumers may wonder why an ingredient list no longer contains the name of a familiar microbe and therefore have doubts about the content of the product,” the team said.

The paper reports that scientific literature surveys will need to account for both the historical and new genus names, while the residual use of the historical names is likely to occur in many books.

“Lawyers or scientists involved in the validation of patent applications or trademarks may be confronted with the same issue for many years to come,” the authors noted. “Patent officers will not find prior art for the new bacterial genera and the risk exists that in this way existing patents may be undermined.”

“This risk is real, as according to Espacenet there are more than 10.000 patents with the term ‘Lactobacillus’ in the title or the abstract.”

The IPA added that all new scientific articles and patent applications should use the new names, and that clear communication should be prepared for regulatory authorities, the medical community, media and, consumers to reflect the changes.

Additionally, EFSA, Health Canada and the FDA have confirmed they will use the new names in their literature and communications, including the QPS list.

“While all these issues seem quite alarming, the general impression, based on experiences in the past, was that the impact of the name change could be manageable with time and dedicated resources but will have a significant cost for companies,” said Pot and colleagues.

While the new names should be used from now on, and many experts recommend using them in conjunction with the old name in technical publications, the group working on reclassification say they have made significant effort to create names for the new genera with commercially relevant strains that still start with the letter L. – adding that most will retain a resemblance of Lactobacillus.

For example, while technical documentation will need to state full names, product packaging that that listed Lactobacillus reuteri as L. reuteri will still be able to do so since the new classification as Limosilactobacillus reuteri will mean the shortening to L. reuteri is still applicable. This is the case for most commercially important strains of bacteria.

Multiple institutions are now hosting a web tool that allows researchers, industry or consumers to check how the taxonomy update affects them by inputting the previous names, which will bring up the new names of the bacteria.

To find out the new genus name of strains that are important to you, use the web tool hosted here, or here and here.

How big is the impact?

According to Ewa Hudson, Director of Insights at Lumina Intelligence, the vast majority of finished products that contain a probiotic ingredient will be impacted – with 86% of all products globally containing a Lactobacillus strain. This compares to around 58% of products that contain a Bifidobacteria strain.

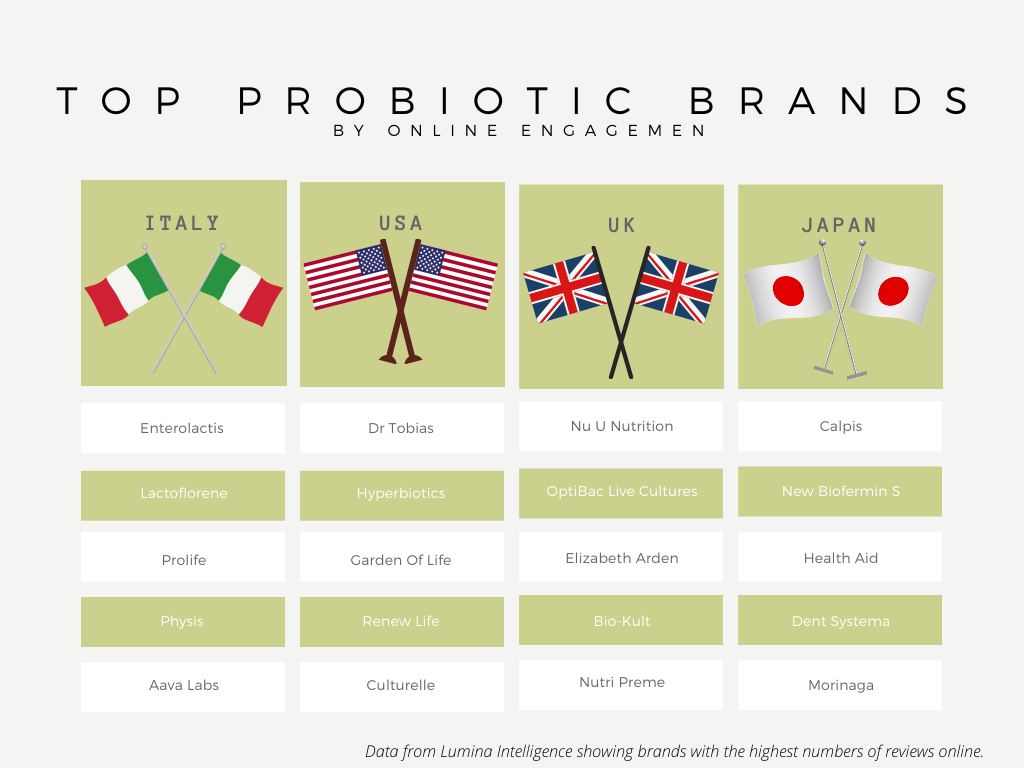

In Europe, Lumina says 82% of all products it captured contained Lactobacillus strains. However, Hudson noted there is a massive amount of fragmentation in the market, with many different brands present as market leaders in many different countries – and very few brands present in multiple territories.

“This is important when we consider how to ensure the changes are represented with these products that are present only in one country,” she noted. “It’s relatively easy for a big company to change packaging for a global brand. But when the market is fragmented with lots of smaller players then there are challenges.”

Hudson questioned whether the multiple companies and brands will all follow the new rules, and whether changes to packaging and labels will be as quick as many hope – especially given the high cost of design and fact that many companies will have several months of stock ready and in storage.

“Communication about the change of taxonomy will require a deep penetration within each country, within numerous communities and small domestic manufacturers may find the impact hitting hard,” Hudson told Microbiome Post.

“Our data shows that 82% of all brands globally will need to have changes to packaging, labelling, and other documentations,” said Hudson. “Having said that, almost 40% of products sold are made in the USA, so the US players will have to be in the driving seat when it comes to both B2B and B2C communication.”

Challenges … and opportunity

Experts are in agreement that it is vital to remind industry and consumers that the actual bacteria in products will remain the same after these name changes are implemented, but product labels will be updated to reflect the new groupings.

“It will be important to take in consideration the new names for the purpose of publication and filing patents, while literature searches should include both,” said Vinot. “A challenge will be to link the new names to studies published with the former ones, and to reassure the consumers that the strains are the same, as is their efficacy and safety.”

It will be vital for brands and retailers reiterate to consumers that the bacteria in products will be the same – since a change of name may cause confusion – she added.

However, ISAPP reiterated that since only genus names are affected – and many new genus names were deliberately chosen to begin with the letter ‘L’ – most products will remain easy to recognize.

While implementing the changes needed from the taxonomy update will no doubt provide a challenge for the industry in the coming months, it will also provide opportunity to better organise and understand the mechanisms and effects of specific probiotic strains.

“The change is also source of opportunity for a better ecological and functional understanding of the bacteria, since how they are related will be more accurate, and new genera share specific traits, to be found all in one place,” said Vinot.

What next?

While there are a great deal of challenges, opportunities, and costs involved in the current update to the Lactobacillus taxonomy, experts agree that it is vital to the future of the scientific discovery – and commercialisation – of the sector.

“The recent finding of 25 new bifidobacterial species in non-human primates is a clear sign that the discovery of the bacterial diversity and therefore the extension and finetuning of the bacterial taxonomy and nomenclature is only at its beginning,” said Pot and colleagues.

“It is to be expected that new species, new genera and even new families will be described in fields that are relevant for the food business or crucial in human and animal health or disease considerations.”

Furthermore, it is widely expected that following the taxonomic update for Lactobacillus, there will be a movement to implement similar reforms to the Bifidobacterium genus in the not-too-distant future.

“Whatever the learnings are for the Lactobacillus taxonomy update, it will be important that they are applied when the next taxonomy update – suggested for Bifidobacteria – takes place,” commented Hudson.

Sign up for free Industry Newsletter