• Fungal migration

• Yeast culprit

• Triggering inflammation

What is already known on this topic

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is an aggressive form of cancer that kills most people within two years of diagnosis. Previous studies have shown that the bacterial component of the microbiome is often altered in this cancer. But little is known about the role of the community of fungal species, known as the mycobiome.What this research adds

By analyzing mice and people with pancreatic cancer, researchers found that some fungi travel from the gut to the pancreas, where they trigger changes in an immune system protein that promotes inflammation and cancer development. Mice treated with a wide-spectrum antifungal drug had tumor weight reduced by up to 30% over 30 weeks.Conclusion

Although more work is needed before the new findings can be applied in treating people with cancer, the study suggests that the mycobiome may be a new target for therapeutic agents.

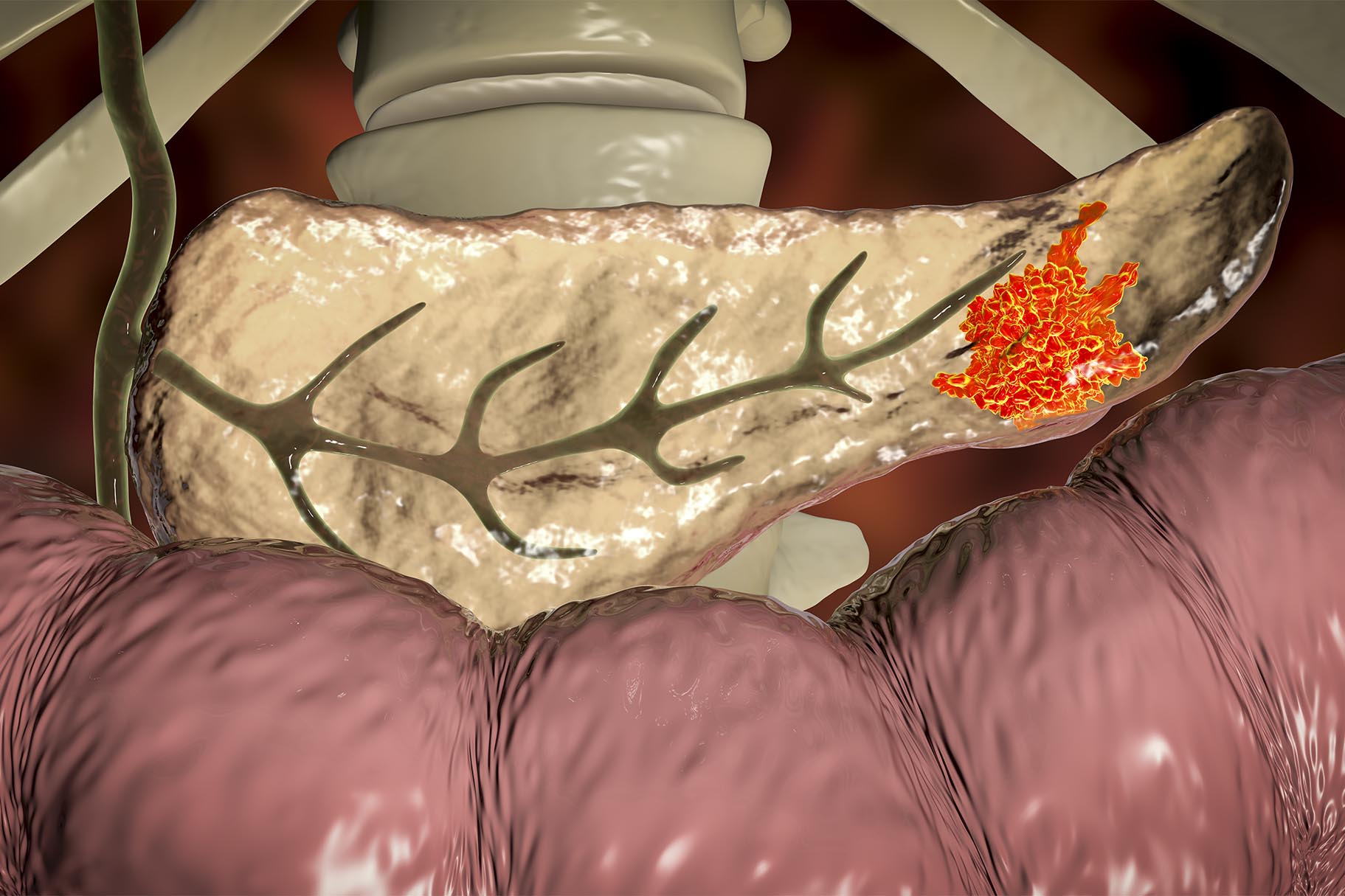

Certain fungi move from the gut to the pancreas, where they can trigger pancreatic cancer growth, according to new research. The study, published in Nature, is the first to show that the community of fungal species in the pancreas – known as the mycobiome – can influence the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Most people with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma usually die within two years of diagnosis, and only about 1 in 10 live longer than five years. And while several studies showed that the bacterial component of the microbiome is often altered in this type of cancer, little is known about the role of the mycobiome.

Berk Aykut and Smruti Pushalkar at New York University School of Medicine and their colleagues set out to assess whether fungi could colonize the pancreas and promote cancer growth.

Fungal migration

The researchers analyzed tumor samples from mice and people with pancreatic cancer to search for fungi-specific DNA markers. The team found that both people and mice had an increased fungal colonization of the pancreas compared to their healthy counterparts.

To find the source of these fungi, the researchers introduced a fungal strain tagged with a fluorescent molecule into the guts of mice. As early as 30 minutes later, the team could detect those fluorescent fungi in the rodents’ pancreas.

Yeast culprit

In mice engineered to express a cancer-causing protein only in the pancreas, the pancreas mycobiome was different from the gut mycobiome. In particular, the yeast Malassezia was more prevalent in pancreatic tumors than in the guts of the engineered mice or the pancreas of healthy rodents. The same yeast strain was also common in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma samples from people. What’s more, in pancreatic tumors the team detected increased levels of Parastagonospora, Saccharomyces, and Septoriella fungi.

Mice treated with a wide-spectrum antifungal drug had tumor weight reduced by up to 30% over 30 weeks. The anti-fungal also increased the anti-cancer effect of a common chemotherapy drug. However, if the animals were colonized with Malassezia after the treatment, their pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma started to grow again, up to 20% faster.

Triggering inflammation

In people, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is associated with the expression of a protein called mannose-binding lectin, which binds carbohydrates on the surface of microorganisms and triggers inflammation, which has been linked to tumor development.

In mice engineered to lack mannose-binding lectin, cancer progression in the pancreas was delayed, even in the presence of Malassezia. This suggests that Malassezia promotes cancer progression by triggering pancreatic inflammation.

Although more work is needed before the new findings can be applied in treating people with cancer, the study suggests that the mycobiome may be a new target for therapeutic agents.