What is already known

Flagellins are a class of structural proteins of the flagellum — a filament that bacteria use to move around. Flagellins are one of the immune system’s main targets, as the proteins are found in both harmful and beneficial gut microbes. But commensal bacteria producing flagellins usually avoid immune surveillance — a phenomenon that is poorly understood.

What this research adds

Researchers analyzed 40 of the most common flagellin types within a database of human gut metagenomes. They found that these flagellins bind to specific immune receptors, but they do not cause a strong activation of the receptors. That’s because ‘silent’ flagellins lack a specific domain that binds a secondary site of the immune receptors that triggers immune responses. Silent flagellins are more common in the gut microbiota of non-industrialized populations compared with that of industrialized populations.

Conclusions

The findings provide a mechanism that explains how the immune system tolerates flagellins of commensal bacteria while mounting an immune response against flagellins produced by pathogens.

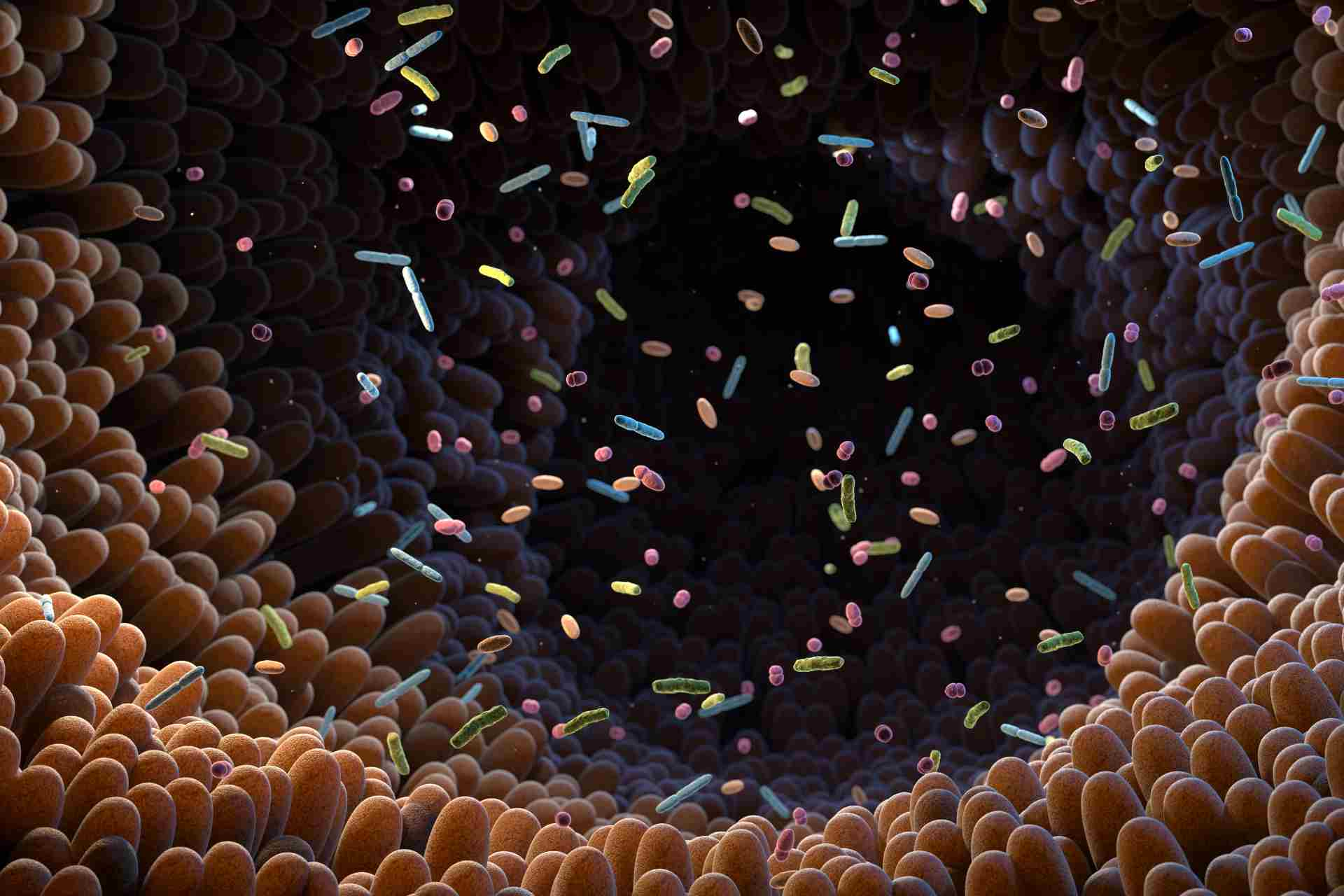

Our immune system can mount powerful responses against pathogens, but it usually doesn’t react to commensal bacteria. New research has revealed that some gut microbes can avoid immune surveillance thanks to the structure of their flagellin proteins — key components of the hair-like filament that allows bacteria to move around.

The findings, published in Science Immunology, provide a mechanism that explains how the immune system tolerates flagellins from commensal bacteria while mounting an immune response against flagellins produced by pathogens.

Flagellins are one of the immune system’s main targets, as the proteins are found in both harmful and beneficial gut microbes. These proteins are recognized by an immune receptor called Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5). When TLR5 binds flagellin, it triggers a cascade of cellular processed, including the production of inflammatory molecules. However, how commensal bacteria that produce flagellins avoid immune surveillance remains poorly understood.

To address this question, Ruth Ley at the Max Planck Institute for Biology and her colleagues analyzed 40 of the most common flagellin types within a database of human gut metagenomes.

Silent flagellins

More than 5,000 proteins encoded by the human gut microbiota were classified as flagellins, and most were produced by Lachnospiraceae, a common type of gut bacteria that includes beneficial microbes such as Roseburia and Eubacterium, the researchers found.

Flagellins produced by gut bacteria were able to bind TLR5, but they stimulated only weakly the receptor. The team dubbed these proteins ‘silent’ flagellins, in reference to their inability to activate TLR5 despite binding it.

Further experiments showed that silent flagellins lack a specific domain that binds a secondary site of TLR5 that triggers immune responses. This allows the immune system to tolerate silent flagellins from commensals yet remain responsive to flagellins from pathogens, the researchers say.

Population differences

Next, the researchers assessed how common silent flagellins are in the human microbiota. Metagenomes from non-industrialized populations had a greater proportion of silent flagellins compared with metagenomes from industrialized populations, the team found.

“The decrease in flagellin abundance with industrialization was most pronounced for the silent flagellins,” they say. “Reduced flagellin diversity may reflect shifts in host-microbiome interactions associated with industrialization.”

The findings shed light onto the flagellin-TLR5 interaction, which has been implicated in several conditions, including bacterial infections and inflammatory bowel diseases.