Cardiovascular diseases, which include stroke and heart attack, are one of the leading cause of death worldwide, but the mechanisms behind these disorders are unknown. Now, researchers have found that a bacterium commonly found in the gut could enter the blood circulation, triggering the formation of blood clots in vessels that carry oxygen and nutrients to the heart.

The findings, published in the European Heart Journal, suggest a new mechanism that could favor heart attacks. They also open up therapeutic avenues to treat this condition, the researchers say.

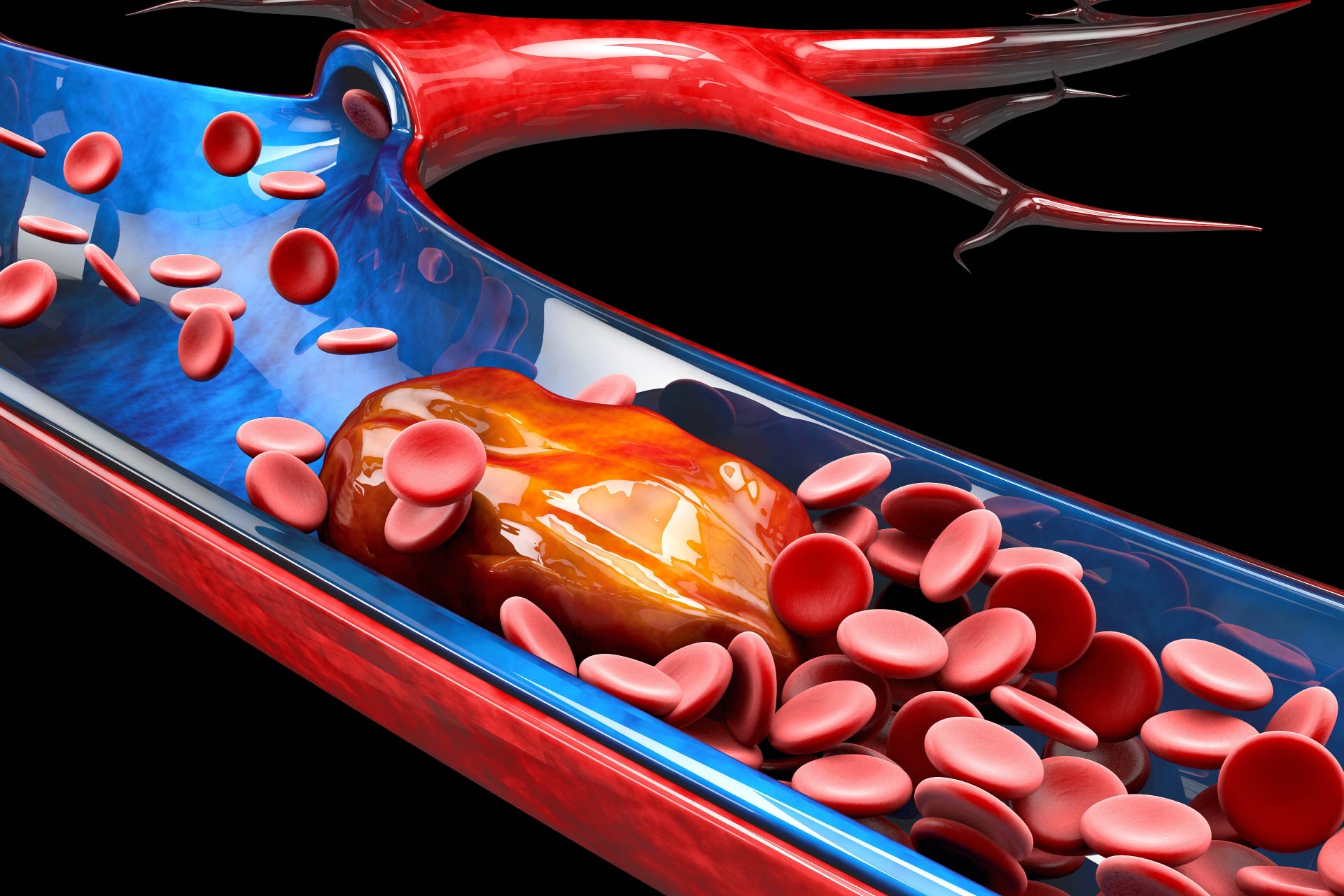

Most heart attacks result from the formation of a blood clot that obstructs one or more coronary arteries. Low levels of microbial molecules called endotoxins have been found in the blood of people whose coronary arteries are obstructed by blood clots, but the role of endotoxins in the formation of blood clots is still unclear.

To address this question, Francesco Violi at Umberto I University Hospital in Rome and his colleagues analyzed blood samples from 150 people, including 50 individuals affected by heart attack. From these individuals, the researchers also obtained samples of coronary blood clots.

Clotting activation

The analysis showed that endotoxins derived from Escherichia coli, a bacterium commonly found in the gut, circulate in the blood of people with heart attack. That’s likely because the intestine of these individuals is more permeable that the gut of healthy people, the researchers found.

The increased gut permeability observed in people with heart attacks could allow endotoxins as well as gut bacteria to enter the blood circulation. Indeed, the researchers found that 34% of samples from people with a heart attack contained E. coli DNA, compared to 4% of samples from healthy people.

The presence of low levels of endotoxins in the blood appears to trigger the formation of coronary blood clots through several mechanisms, the researchers found. These include the activation, adhesion, and aggregation of small cell fragments known as platelets, which help to turn blood from a liquid into a gel.

Therapeutic approach

To trigger the formation of blood clots, E. coli appears to bind to a specific cell-surface receptor called TLR4. The team also identified a molecule that inhibits the TLR4 receptor, hindering the formation of blood clots.

Mice injected with E. coli or treated with endotoxins developed more blood clots than untreated mice. But the detrimental effect of endotoxins disappeared when mice were given the TLR4 inhibitor.

The results could help to develop new therapeutic strategies that rely on TLR4 inhibition to counteract the formation of coronary clots in people with cardiovascular disease, the researchers say.