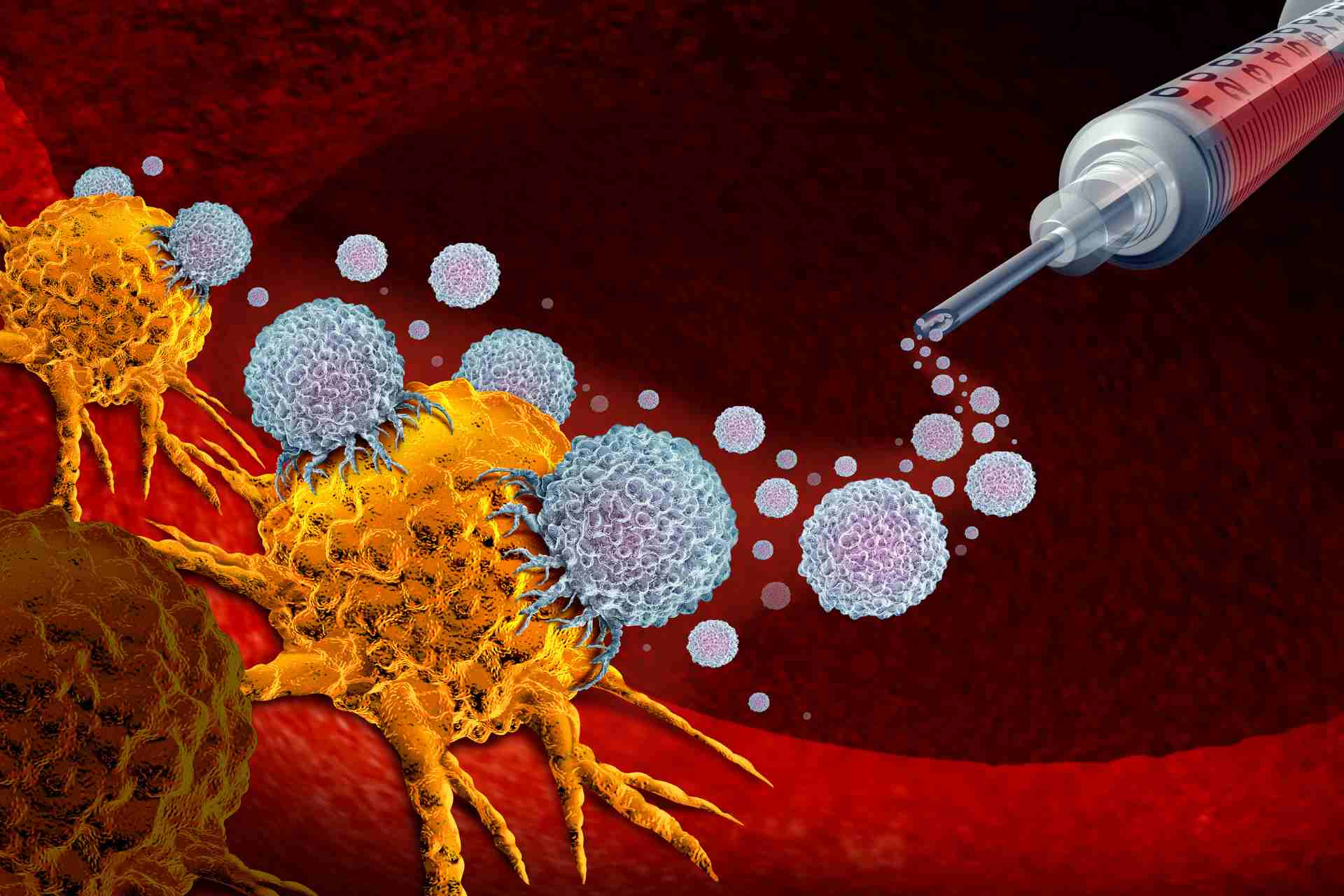

The effectiveness of immunotherapy — a type of cancer treatment that helps the body’s immune system recognize and destroy tumors — has been associated with a person’s gut microbiota. Now, researchers have found that certain microbial species in the gut can boost the effectiveness of this therapy by increasing the activity of specific immune cells.

The findings, published in Med, suggest that the presence of specific microbes in the gut microbiota can serve as biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of immunotherapy.

A person’s gut microbiota includes bacteria and other microbes such as fungi, protozoa, and viruses. While some of these microbes have been linked to better immunotherapy response, their role is not well understood. That’s because studies on the gut microbiota’s link to immunotherapy response often focus on single cancers, lack consistency, and are affected by factors such as diet, the researchers say.

To identify microbial patterns that could predict immunotherapy success, the team — led by Yufeng Lin at the Chinese University of Hong Kong — set out to analyze stool samples from more than 1,359 people with various cancer types, including melanoma, lung, kidney, and liver cancer.

Microbial signatures

Treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) did not dramatically alter the microbiota composition of study participants, but the researchers found differences in the diversity of gut microbes between people who responded to ICIs and those who didn’t. They identified 55 species — including bacteria, fungi, and viruses — that were associated with positive outcomes.

Certain microbes found in ICI responders were linked to these individuals living longer without their cancer getting worse, regardless of their age, gender, or cancer type. For example, in people with melanoma, the bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii was associated with better outcomes, while in people with lung cancer, a mix of bacteria and a virus were linked to improved survival.

The analysis revealed that specific microbial signatures could predict ICI response, suggesting that the presence of certain bacteria and other microbes could help inform cancer treatments in the future, the researchers say.

Predicting responses

Next, the researchers set out to validate their findings in mice. Two bacteria, F. prausnitzii and Coprococcus comes, reduced tumor growth in mice with melanoma and lung cancer, and they boosted the activation of immune cells that kill cancer cells, especially when combined with immunotherapy. Similarly, the fungus Nemania serpens and the yeast Hyphopichia pseudoburtonii also improved immune responses, reducing tumor growth when paired with ICIs.

Using statistical models, the researchers could predict ICI response based on the presence of certain microbial species. The models were accurate at predicting response across three types of cancer — melanoma, lung, and kydney.

“Altogether, our results highlighted the pivotal involvement of trans-kingdom microbes in ICI treatment, therefore providing insights into the development and implementation of innovative cancer immunotherapy,” the authors say.