• Ancient microbes

• Modern diseases

What is already known on this topic

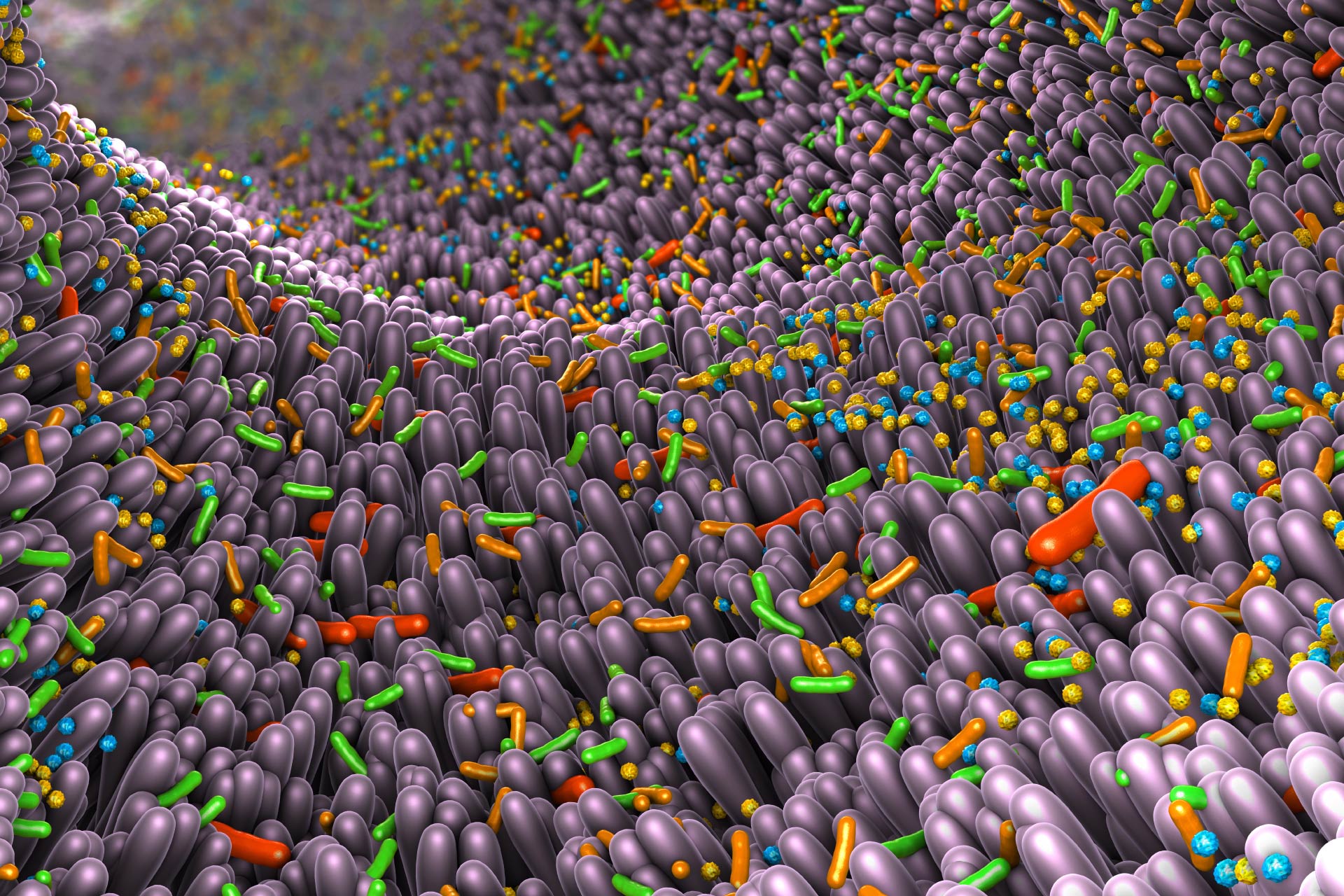

Several studies have shown that people living in industrialized societies have a less diverse gut microbiota than individuals from non-industrialized populations. The industrialized microbiota has also been linked to an increase in the incidence of chronic illnesses such as obesity and autoimmune diseases. But how the gut microbiota evolved over time remains a mystery.What this research adds

Researchers have analyzed human feces from around 1,000-2,000 years ago that had been found in southwestern USA and Mexico. From these samples, the team reconstructed nearly 500 microbial genomes, of which 181 appear to be of human gut origin. About 40% of these genomes had never been described before, suggesting the presence of species that are different from those seen in modern populations. By comparing the genomes of these microbes to those of present-day gut microbiota from industrial and non-industrial populations, the researchers found that ancient microbiotas are similar to those of modern-day individuals from non-industrialized societies.Conclusion

The findings shed light on the evolutionary history of the human microbiota and could help to understand the role of gut microbes in health and disease.

Over the past 2,000 years, the communities of microbes inhabiting the human microbiota underwent substantial changes, which may explain how the composition of present-day gut microbiota is linked to the development of long-term diseases. That’s the conclusion of an analysis of ancient feces from North America.

The findings, published in Nature, shed light on the evolutionary history of the human microbiota and could help to understand the role of gut microbes in health and disease, the researchers say.

Several studies have shown that people living in industrialized societies have a less diverse gut microbiota than individuals from non-industrialized populations. The industrialized microbiota has also been linked to an increase in the incidence of chronic illnesses such as obesity and autoimmune diseases. But how the gut microbiota evolved over time remains a mystery.

“When we study people today — anywhere on the planet — we know that their gut microbiomes have been influenced by our modern world, either through diet, chemicals, antibiotics or a host of other things,” says study co-author Meradeth Snow at the University of Montana. “So, understanding what the gut microbiome looked like before industrialization happened helps us understand what’s different in today’s guts,” she says.

To reconstruct ancient microbial genomes, a team of researchers led by Aleksandar Kostic at Harvard Medical School analyzed eight well-preserved samples of human feces from around 1,000-2,000 years ago that had been found in southwestern USA and Mexico.

Ancient microbes

From the ancient fecal samples, the researchers reconstructed 498 microbial genomes, of which 181 appear to be of human gut origin. Of these, 61 — or about 40% — had never been described before, suggesting the presence of species that are different from those seen in modern populations.

Next, the team compared the ancient feces to those of individuals from industrialized and non- industrialized present-day populations. The microbial composition of the ancient fecal samples was more similar to those of non-industrialized modern-day samples than to those of industrialized ones. For example, Bacteroidetes and Verrucomicrobia were more common in the samples from industrialized populations than in ancient samples, whereas Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Spirochaetes were less abundant in industrialized samples than in the ancient feces.

The bacterium Treponema succinifaciens wasn’t present in any samples from industrialized populations, but it was present in all of the eight ancient microbiotas analyzed, the researchers found. “In ancient cultures, the foods you’re eating are very diverse and can support a more eclectic collection of microbes,” Kostic says. “But as you move toward industrialization and more of a grocery-store diet, you lose a lot of nutrients that help to support a more diverse microbiome.”

Modern diseases

Further analyses showed that both modern-day gut microbiotas from industrialized and non-industrialized populations harbored more antibiotic-resistance genes than did ancient fecal samples. Modern samples also had higher numbers of genes that produce proteins that degrade the intestinal mucus layer. Degrading the protective mucus layer of the gut can result in inflammation, which is associated with various intestinal diseases.

On the other hand, ancient fecal samples and samples of individuals from non-industrialized societies harbored several genes associated with the metabolism of starches — likely because these populations consume more complex carbohydrates than do modern-day industrial populations.

Studying the microbes found in the ancient fecal samples could help to combat diseases, such as diabetes, that are common in industrialized societies, the researchers say.