What is already known on this topic

Recent studies have shown that the gut microbiota can influence the effectiveness of a type of anti-cancer treatment known as immunotherapy. In particular, Akkermansia muciniphila has been associated with clinical benefits in people with certain cancers who were treated with a class of immunotherapy drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, there are no biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in people with non-small-cell lung cancer.

What this research adds

Researchers analyzed the gut microbiota of 338 people with non-small-cell lung cancer who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. People with Akkermansia in their guts responded to therapy better than those with undetectable levels of the bacteria. They also lived longer than those without detectable Akkermansia. However, people with low levels of Akkermansia tended to survive longer than those with high or undetectable levels of the microbe. What’s more, people who had not taken antibiotics in the two months before anti-cancer treatment had better survival than those who took antibiotics, regardless of whether they had detectable Akkermansia.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that Akkermansia can be used as a biomarker to identify who is likely to respond to treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

In recent years, immunotherapy has become a common treatment for many types of cancer. However, this therapeutic approach doesn’t yet work for everyone. A study on people with non-small-cell lung cancer suggests that the gut microbe Akkermansia muciniphila can be used as a biomarker to identify who is likely to respond to immunotherapy.

The findings, published in Nature Medicine, confirm previous observations made in smaller group of people with non-small-cell lung cancer and show that the gut microbiota, especially the abundance of Akkermansia, could help to predict survival of these cancer patients.

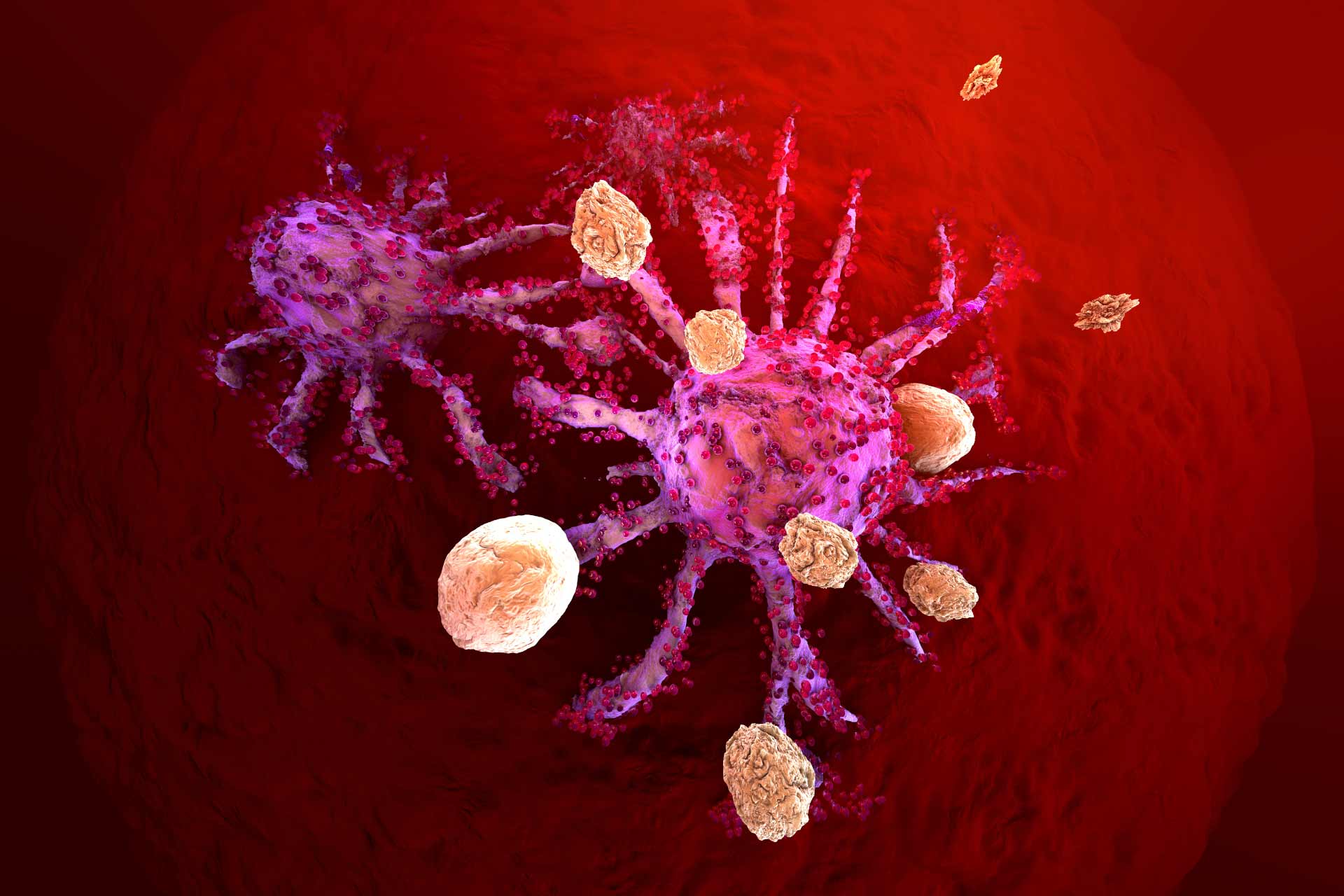

Immunotherapy works by triggering a person’s immune system to attack tumor cells. Immunotherapy drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors act as brakes to prevent immune cells from attacking healthy cells. These drugs have proven effective for treating several types of cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer and kidney cancer. However, there are no biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in people with non-small-cell lung cancer.

Previous studies by Laurence Zitvogel at the Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus and her colleagues have shown that Akkermansia is associated with clinical benefits in cancer patients who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Now, the researchers set out to explore whether the presence of Akkermansia could become a biomarker for predicting survival rate and response to therapy in people with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer.

Relative abundance

The researchers analyzed the gut microbiota of 338 people with non-small-cell lung cancer who were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. People with Akkermansia in their guts responded to therapy better than those with undetectable levels of the bacteria.

People with Akkermansia also survived longer than those without detectable Akkermansia, 18.8 versus 15.4 months. However, people with an overall survival of less than 12 months had high levels of detectable Akkermansia in their guts, which suggests that the relative abundance of Akkermansia may influence health outcomes more than the microbe’s absolute presence.

Indeed, people with low levels of Akkermansia tended to survive about 27.2 months — much longer than those with high or undetectable levels of the microbe, the researchers found.

Microbial biomarker

The researcher also looked at the effects of antibiotic use on clinical outcome. People who had not taken antibiotics in the two months before anti-cancer treatment had better survival than those who took antibiotics, regardless of whether they had detectable Akkermansia.

The team also found that antibiotic use was accompanied by a dominance of Akkermansia and the presence of Clostridium bacteria, which are both associated with resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

The findings suggest that future trials designed to discover biomarkers for responses to immunotherapy in cancer patients should quantify the relative abundance of Akkermansia and assess the patients’ use of antibiotics. “Our study provides a strong rationale for the development of diagnostic tools for assessing gut dysbiosis for routine oncological management, as well as a framework for the design of microbiota-centered interventions to circumvent primary resistance to [immune checkpoint inhibitors] in patients with [non-small-cell lung cancer],” the authors say.