What is already known

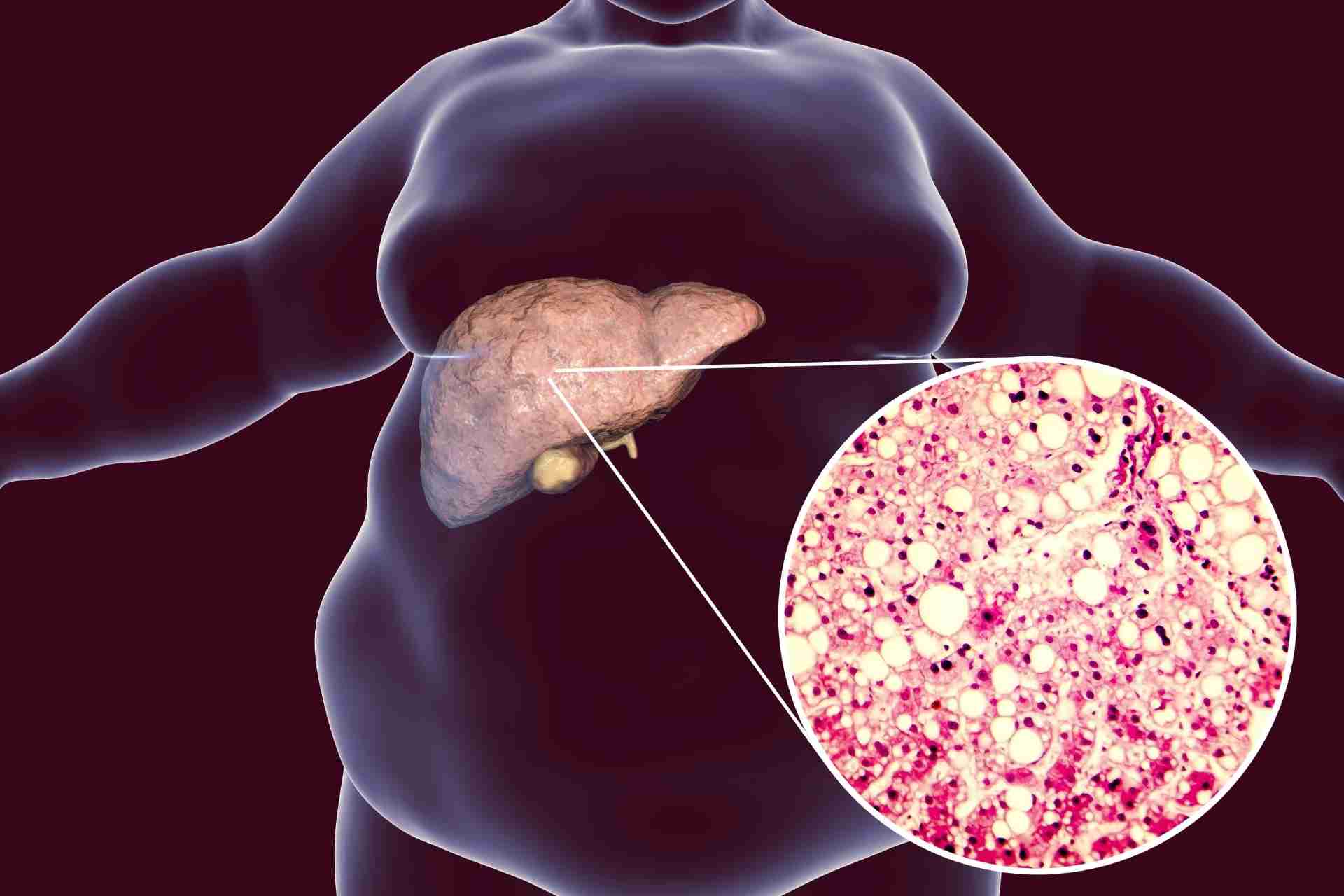

About 25% of the global population is affected by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a range of conditions caused by a build-up of fat in the liver. Although early-stage NAFLD is not usually harmful, it can lead to liver-scarring, liver cancer or liver failure, if undetected. Studies have shown that gut microbes contribute to the development of NAFLD, but it’s unclear whether the microbiota composition of a healthy person could predict whether or not they would develop NAFLD in the future.

What this research adds

Researchers followed hundreds of people for about four years after an initial screening for NAFLD. They also analyzed data from 90 people who went on to develop NAFLD and 90 who didn’t. Those who developed NAFLD had low levels of specific gut bacteria, including Methanobrevibacter, Dorea formicigenerans and Slackia, as well as high abundances of amino acids and the gut metabolite oxoglutaric acid, which has been associated with diabetes, obesity and NAFLD — among other conditions. The team used these microbial signatures to classify with high accuracy people who developed NAFLD and those who didn’t.

Conclusions

The findings reveal the microbiota alterations during NAFLD and suggest that gut microbes can be used as an early clinical sign of the condition.

About 25% of the global population is affected by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a range of conditions caused by a build-up of fat in the liver. A large clinical study now found specific microbial signatures that may help to predict who is more likely to develop NAFLD.

The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine, reveal the microbiota alterations during NAFLD and suggest that gut microbes can be used as an early clinical sign of the condition.

“I see microbiome-based diagnostics as something that will reach clinical practice and have great potential in the next ten years,” says co-senior study author Gianni Panagiotou at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology–Hans Knöll Institute.

NAFLD is not caused by high alcohol consumption but it is typically seen in overweight or obese people. Although early-stage NAFLD is not usually harmful, it can lead to liver-scarring, liver cancer or liver failure, if undetected. Studies have shown that gut microbes contribute to the development of NAFLD, but it’s unclear whether the microbiota composition of a healthy person could predict whether or not they would develop NAFLD in the future.

To assess the prognostic value of gut microbes, Panagiotou and his colleagues followed hundreds of people for about four years after an initial screening for NAFLD.

Bacterial signatures

In 2014, the researchers screened about 2500 participants with a diagnostic test for NAFLD. Of those, 1216 participants didn’t show any symptoms of NAFLD. But at a follow-up visit in 2018, 90 people were diagnosed with NAFLD. These people were matched with 90 individuals who did not have NAFLD neither at the initial clinical visit nor at the follow-up visit.

People who developed NAFLD had low levels of specific gut bacteria, including Methanobrevibacter, Dorea formicigenerans and Slackia, the researchers found. Dorea formicigenerans is known to be abundant in people with obesity, and Slackia levels are usually higher in people with moderate to severe fibrosis than in those with mild or no fibrosis.

In people who developed NAFLD, the team also found various metabolic shifts, including high levels of amino acids and the gut metabolite oxoglutaric acid, which has been associated with diabetes, obesity and NAFLD — among other conditions.

Predicting NAFLD

Finally, the researchers developed a machine-learning model that used these microbial signatures to predict which individuals are more at risk of developing NAFLD. The model could classify with an accuracy of about 71% people who developed NAFLD and those who didn’t.

The team also validated their results with data from studies done in the US and Europe. “The model we developed combines easily measurable information from the blood with data from the microbiome and can thus increase the reliability enormously,” Panagiotou says.

Although larger studies will help to improve the model’s generalizability and accuracy, the findings suggest that microbiota signatures could be used as a minimally invasive test to help diagnose NAFLD, the authors say.