Not long ago, during a medical conference, I asked the audience: When do you think the first probiotic product was introduced to the market?

The answers varied, but all suggested a date no earlier than the 1950s.

The correct answer, however, dates back more than a century: it was around 1907–1908 that Lactobacilline, a true forerunner of modern probiotics, was created by the brilliant Nobel Prize-winning scientist Élie Metchnikoff.

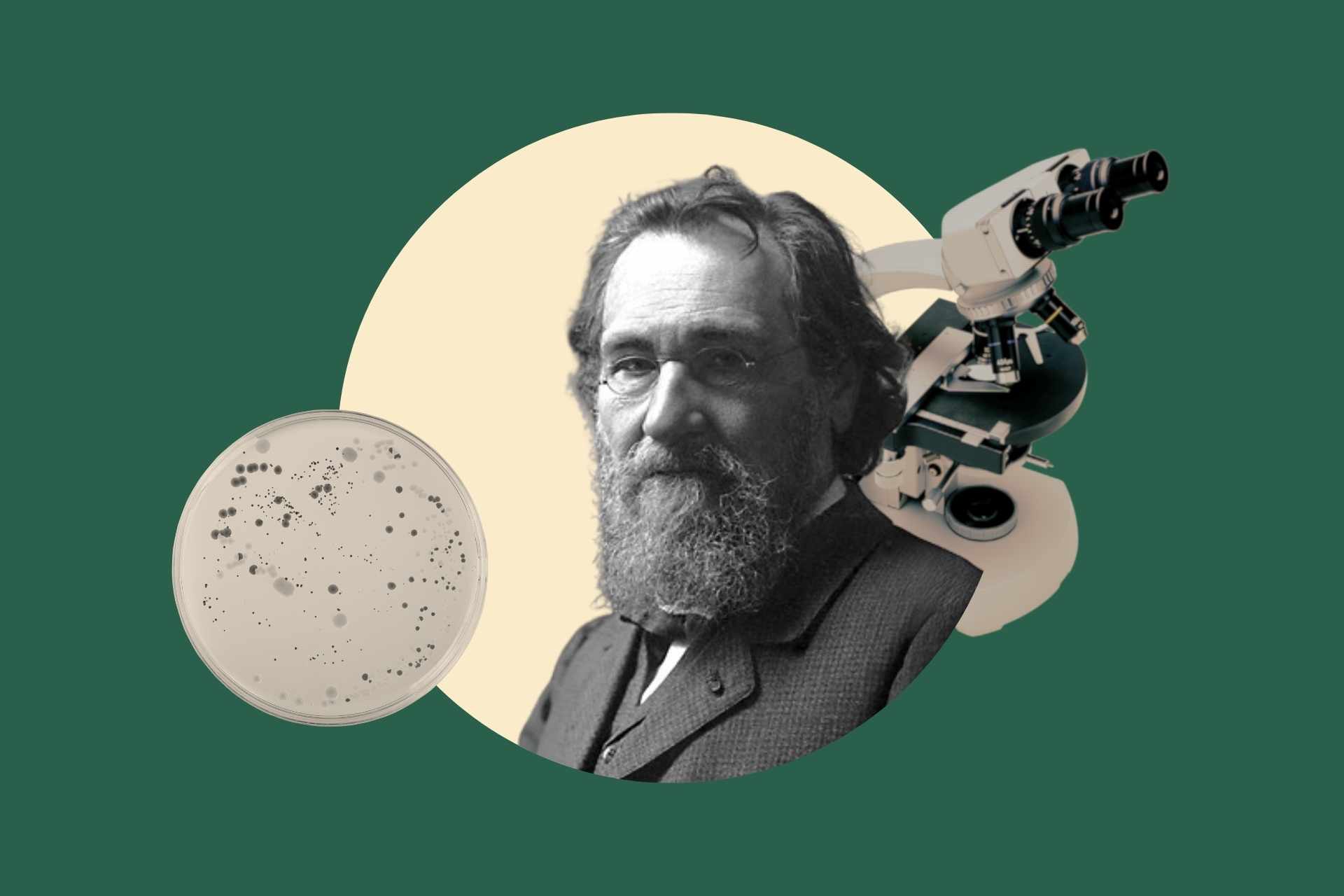

This year marks the 180th anniversary of Metchnikoff’s birth (May 16, 1845, in Kharkiv, Ukraine). He is widely considered the father of immunology, the inventor of the term gerontology, and a pioneer of what would become known as the “science of longevity.” He was also the first to experiment with using “beneficial” bacteria to counteract pathogenic microbes. The recent rediscovery of a key, long-forgotten text of his offers the perfect opportunity to honor his groundbreaking contributions.

But let’s take things in order.

When Metchnikoff arrived at the Institut Pasteur in Paris in 1888, he already had years of research behind him, particularly his work in Messina starting in 1882 on protozoa and phagocytes. This research laid the foundation for immunology and would eventually earn him the Nobel Prize in 1908.

At the Pasteur Institute, Metchnikoff quickly immersed himself in microbiological studies, the core focus of the prestigious research center. He became fascinated by the bacterial population of the human gut, proposing an early hypothesis about the link between the type of bacteria inhabiting our digestive system and our overall health—especially our ability to defend against pathogenic invaders.

In 1901, Metchnikoff was awarded the Wilde Medal in England, an honor conferred by the Royal Society of Arts (RSA).

It is the speech he delivered during this award ceremony—the text recently “brought back to light” by my friend Massimo Barberi, who found it in a bookstore in Shropshire, England—that is the focus of this editorial.

Reading the 38 pages of this speech is a stunning experience.

Metchnikoff outlines a “research program” that remarkably anticipates many of the topics that researchers are still exploring today.

He begins with a detailed account of how newborns are first colonized by bacteria from their mother and environment. He follows with an incredibly detailed characterization of the stomach’s microflora—insightful even by today’s standards.

He goes even further, describing the skin’s microbiota—an area that probiotic researchers have only recently begun to explore—mentioning Malassezia, the agent of dermatitis, which he refers to as the “bottle bacterium.”

Metchnikoff also provides a thorough description of the digestive tract’s microflora, starting from the oral cavity and focusing in particular on the stomach, where he notes the dominance of “sarcinae”—perhaps an early observation of Helicobacter pylori, now known to cause ulcers.

He dedicates several pages to distinguishing the microbial populations of the small and large intestines, noting significant differences between the two ecosystems.

He even mentions Bacillus bifidus (now known as Bifidobacterium), which characterizes the gut flora of breastfed infants.

His conclusion to this section is striking:

“In the current state of science, it is impossible to determine the number of microbial species that make up the flora of a healthy human.”

Only today, with metagenomic techniques, are we approaching a complete description of the gut microbial ecosystem—yet we still have the “Work in Progress” sign hanging outside our labs.

In the following pages, Metchnikoff discusses the relationships between different types of microbes inhabiting the human body. Based on various observations and studies, he argues that certain bacteria (such as those found in sour milk) might inhibit the action of pathogenic bacteria. Although cautious (“This preventive role has never been definitively proven, but it is highly probable”), he is clearly fascinated by the idea.

It is here, in 1901, that the concept of “colonization resistance” is born—the very foundation of the modern concept of probiotics.

Metchnikoff devotes further attention to the role of microorganisms in digestive processes, considering their contribution essential:

“There is no doubt. The animal organism cannot digest food properly without microbial assistance.”

Even today, this insight deserves deeper exploration.

Among his many “brilliant intuitions,” Metchnikoff also highlights the importance of bacterial metabolites. He sees most of these byproducts as toxic and proposes a model of “self-intoxication” to explain several diseases.

Remarkably, Metchnikoff even suggests that bacterial metabolites might influence the development of psychiatric disorders—anticipating, more than a century in advance, the concept of the gut-brain axis that researchers are only now fully developing.

Unfortunately, the speech ends with what today we would consider a scientific misstep:

Metchnikoff believed the colon was useless, if not harmful. Until 1907, he even proposed its surgical removal. Later, he shifted his strategy, advocating the regulation of gut bacteria through the ingestion of “acidifying” bacteria. He founded a company, Le Ferment, which produced an early form of probiotic fermented milk and a powdered product containing a specifically selected lactobacillus strain—effectively the ancestor of today’s probiotic supplements.

Reading this text is not just educational—it’s deeply moving. Thanks to those who brought it back into the light!