What is already known

Inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD, is an umbrella term for a group of chronic inflammatory disorders of the gut, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Although the cause of IBD remains unclear, gut bacteria seem to be associated with the condition. However, antibiotic therapies are not a viable option to treat IBD, as antibiotics kill helpful gut bacteria and give rise to antibiotic-resistant microbes.

What this research adds

Researchers analyzed the gut microbiota of more than 500 people with IBD and compared it to that of healthy people. Those with IBD tended to have high levels of specific strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae in their guts, especially when they experienced disease flare-ups. Transplanting these bacterial strains into mice resulted in severe gut inflammation. The researchers identified a combination of bacteria-infecting viruses, called phages, that could kill the Klebsiella strains without harming helpful gut bacteria. The phage cocktail reduced inflammation and tissue damage in mice. A small trial in healthy people showed that the phages remained active throughout the gastrointestinal tract and were safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that phages can be used to treat IBD and other diseases associated with gut microbes.

More than 3 million adults in the United States have been diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease, or IBD — a group of chronic inflammatory disorders of the gut, including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Now, researchers have found that a specific combination of bacteria-infecting viruses can ease symptoms of IBD in mice. The therapy was safe and well tolerated in early trials on people.

The findings, published in Cell, suggest that bacteria-infecting viruses can be used to treat IBD and other diseases associated with gut microbes. “Our vision is that this new modality could potentially be developed and applied against a number of other IBD-associated bugs, and also against commensals that are involved with other diseases, including obesity, diabetes, cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and more,” says study senior author Eran Elinav at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

Scientists have found that gut bacteria are associated with IBD, though the cause of the disease remains unclear. However, antibiotic therapies are not a viable option to treat IBD, as antibiotics kill helpful gut bacteria and give rise to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

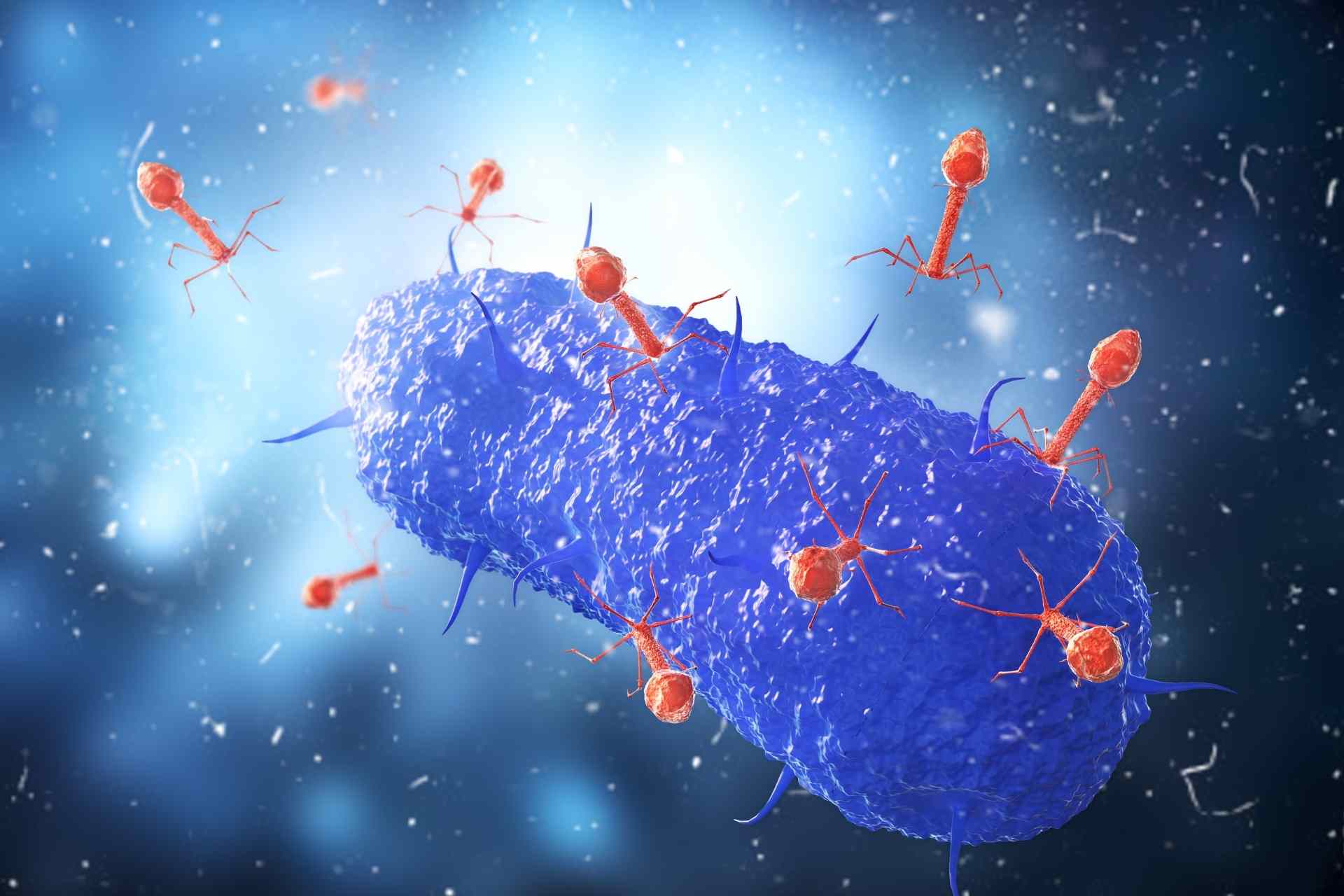

To target and kill only gut bacteria associated with IBD, Elinav and his colleagues turned to phages—a type of viruses that attack only bacteria. Efforts to use phage therapies to treat bacteria-associated diseases have been stymied by the fact that bacteria quickly become resistant, evading the viruses’ attack.

Phage therapy

To identify bacteria that may contribute to IBD, Elinav’s tem collected stool samples from 537 people with IBD from France, Israel, the United States and Germany. Then, they characterized the bacteria in the individuals’ gut microbiota and compared them to those of healthy people.

About 40% of people with IBD had high levels of specific strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae in their guts, especially when they experienced disease flare-ups. Transplanting these bacterial strains into mice resulted in severe gut inflammation, the researchers found.

Next, the team set out to characterize thousands of phages to identify those that were able to kill the Klebsiella strains contributing to IBD in mice. The researchers identified 41 such phages.

Precision therapy

The researchers tested various combinations of phages to find the cocktail that best prevented bacterial growth in mice infected with the Klebsiella strains. In these combinations, each of the phages uses a different mechanism to attack and kill bacteria, making the emergence of resistance unlikely.

The team ended up with a combination of five phages that could kill Klebsiella strains in test tubes. In mice, the phage cocktail suppressed Klebsiella strains without harming helpful gut bacteria, and it reduced inflammation and tissue damage, easing symptoms of IBD.

A small trial in healthy people showed that the phages remained active throughout the gastrointestinal tract and were safe and well tolerated. These results suggest that the phage mixture could be used to treat IBD in humans.

Elinav’s team is now working towards identifying other disease-associated bacteria that could be targeted with a phage combination therapy. “What we envision is a precision medical pipeline,” Elinav says. “Using it, we can characterize the pathogenic bacteria of a person suffering from a disease related to the gut microbiota, and then apply a phage therapy that would be tailored to the individual to suppress the bacteria.”