-

What is already known on this topic

Scientists had long considered the human womb sterile, but recent studies have suggested that the placenta is colonized with bacteria. However, the sterile womb hypothesis is supported by the fact that germ-free mammals can be delivered into sterile isolators as well as by research that showed no difference in terms of microbial abundance between background negative controls and placenta samples. -

What this research adds

To further investigate if the human placenta is sterile and assess whether bacterial colonization of the placenta is associated with preterm birth, the researchers analyzed placenta samples from full-term and preterm deliveries. The team found low bacterial levels in all the placenta samples, and the DNA sequencing analysis revealed that the bacteria found in placenta samples are indistinguishable from those found in negative controls. -

Conclusions

The results suggest that human placenta, either from full-term or preterm births, is not colonized by a consistent microbiota.

The human placenta may be sterile, after all. That’s the conclusion of a study led by Jacob Leiby at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia. The results were published in the journal Microbiome.

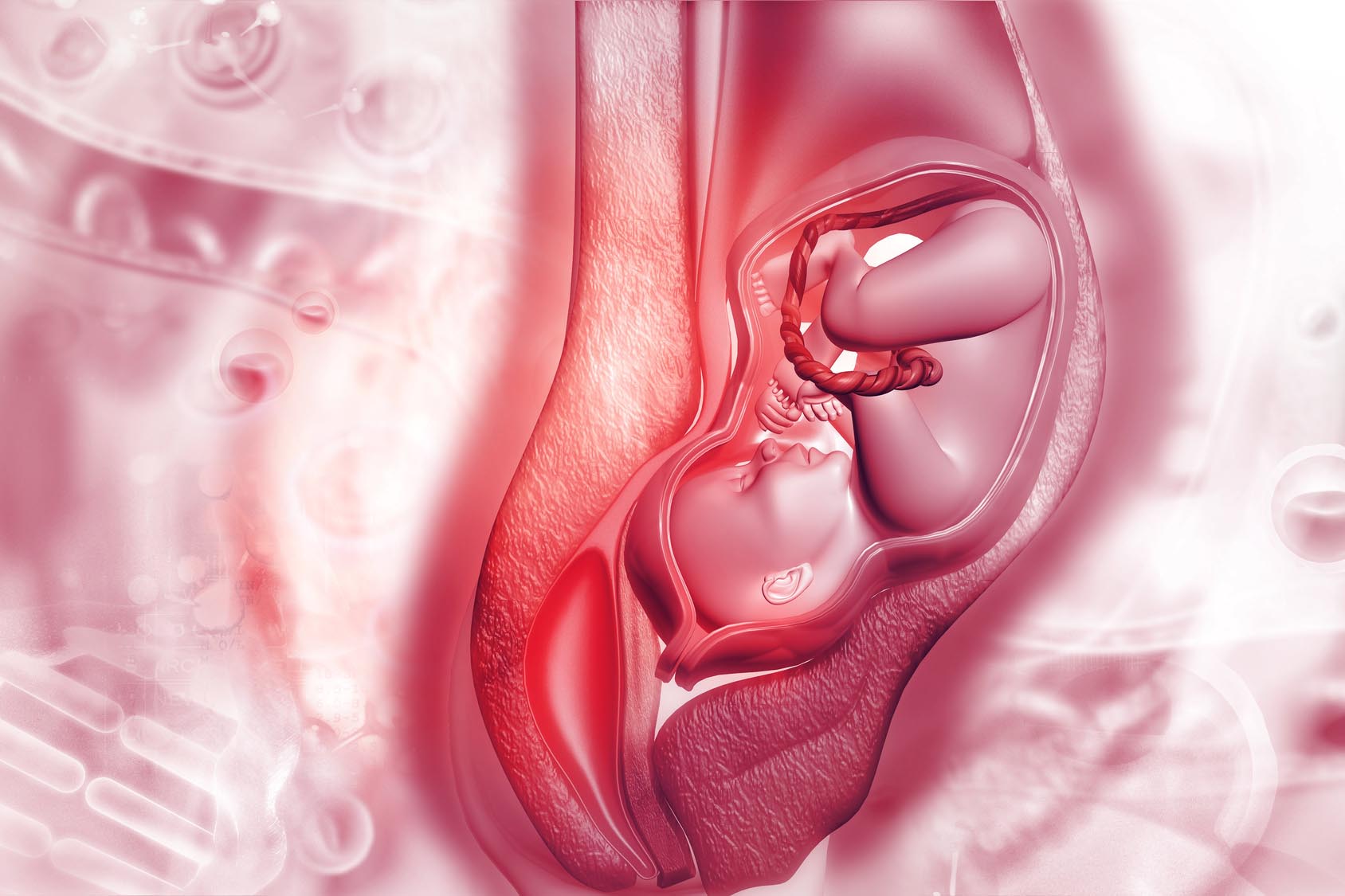

Scientists had long thought that the human womb was sterile in healthy pregnancies, but recent studies have suggested that the placenta has its own microbiota. However, germ-free mammals can be delivered into sterile isolators, supporting the idea that the womb is indeed sterile. What’s more, previous research done by the same group at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine has found no difference in terms of microbial abundance between background negative controls and placenta samples.

To further investigate the sterile womb hypothesis and assess whether bacterial colonization of the human placenta is associated with preterm birth, the researchers analyzed 20 placenta samples from full-term births and 20 from preterm births.

The team used samples of saliva and vaginal fluid from the mothers as positive controls, since these body sites are known to be colonized by several microbial communities. As negative controls, they used swabs that were waved in the air in the laboratory, as well as empty tubes and PCR grade water that were processed with the samples at various steps of the analysis.

Analysis of bacterial abundance

The researchers used 16S rRNA gene qPCR to determine the absolute levels of bacterial DNA in placenta samples, vaginal and oral samples (positive controls), and negative controls. Vaginal and oral samples contained significantly higher concentrations of bacterial DNA than placenta samples, while the two negative controls that contained the lowest concentration of bacterial DNA weren’t significantly different from placenta samples.

The researchers also found no significant differences between placenta samples from full-term and preterm births.

Analysis of bacterial DNA

Next, the researchers used 16S rRNA gene sequencing to analyze the bacterial communities present in the different samples. Vaginal and oral samples contained high proportions of bacteria that are known to be associated with these body sites, including Ureaplasma, Lactobacillus, Neisseria, Streptococcus, and Prevotella. Samples from placenta and negative controls contained high proportions of bacteria usually associated with reagent contaminants, such as Ralstonia and Pseudomonas.

Several bacteria found in vaginal samples, including Ureaplasma and Lactobacillus, were detected in some of the placenta samples. Further analysis showed that these samples derived from vaginal deliveries and not cesarean deliveries.

Overall, the researchers found no significant differences between placenta samples, either from full-term or preterm births.

Analysis of bacterial DNA content

To further analyze the bacterial communities present in the samples, the team used shotgun metagenomics sequencing. Saliva and vaginal samples showed expected bacterial communities, including Prevotella and Lactobacillus, respectively. The most abundant bacteria in placenta samples and negative controls was the contaminant Ralstonia.

Alteromonas mediterranea and Methanosarcina mazei, two other bacteria found at high concentrations in placenta samples, were less abundant in negative controls. However, these bacteria seem to be detected as result of the preparative procedure rather than naturally present in the samples.

The researchers also found no differences in samples from vaginal versus cesarean deliveries, fetal versus maternal side of the placenta, and normal placentas versus cases of infection of the amnion and chorion.

In summary, the study found no evidence of a human placenta microbiota in samples from preterm and full-term births. Placental samples are indistinguishable from negative controls and all the detected bacteria appear to be contaminants from the environment.