What is already known

People living in urban areas are known to have less microbial diversity in their guts than people living in rural areas. Because humans rely on gut microbes to break down dietary fiber from plants, which is beneficial for human health, the lower biodiversity may contribute to the increasing incidence of metabolic conditions in industrial societies.

What this research adds

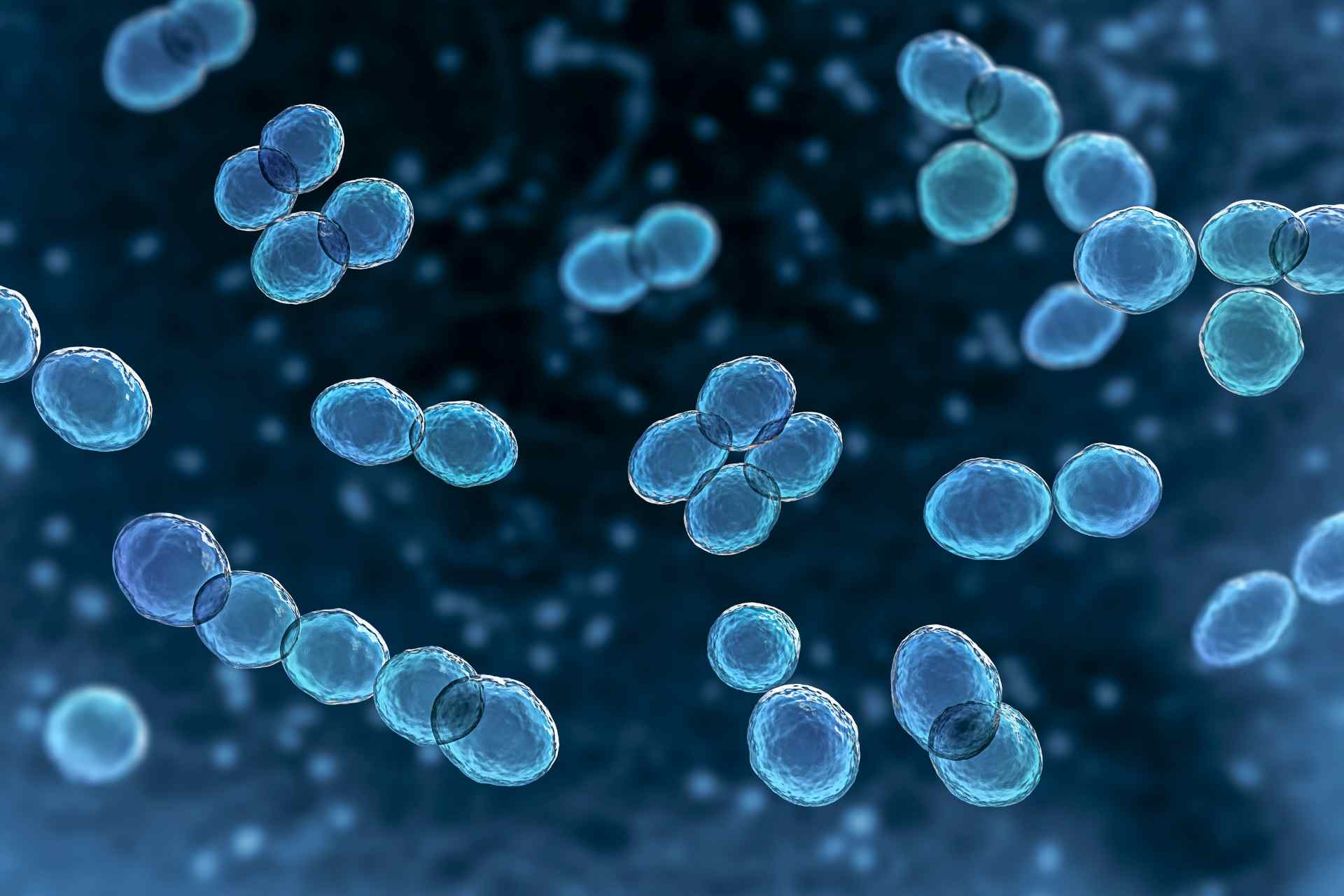

Researchers identified previously undescribed cellulose-degrading microbes within the human gut microbiota. These bacteria, known as Ruminococcus, degrade cellulose by producing large protein complexes called cellulosomes. Cellulosomes attach to cellulose fibers and break them apart. Then, enzymes further disassemble cellulose fibers into shorter chains, which can be digested by Ruminococcus and other gut microbes. Ruminococcus are common components of the human gut microbiota in hunter-gatherer societies and people who live in rural societies, but that they are lacking in people living in industrial societies — likely because these societies are shifting away from a fiber-rich diet.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that Ruminococcus bacteria were more prevalent in ancient human populations and non-industrialized societies, likely due to the high dietary fiber intake. The decline of these strains in industrial societies may impact health, but there’s potential for reintroduction through dietary interventions and probiotics.

Fiber, which is mostly derived from plants and whole grains, helps us maintain a healthy gut microbiota by serving as a source of nutrition for cellulose-digesting bacteria. However, modern dietary habits in industrial societies may be leading to the loss of these beneficial bacteria from the human gut microbiota, according to new research.

The findings, published in Science, suggest that cellulose-degrading microbes were more prevalent in ancient human populations and non-industrialized societies, likely due to the high dietary fiber intake. The decline of these strains in industrial societies may impact health, but there’s potential for reintroduction through dietary interventions and probiotics.

“Throughout human evolution, fiber has always been a mainstay of the human diet,” says study lead author Sarah Moraïs at Ben-Gurion University in Beer-Sheva, Israel. “It is also a main component in the diet of our primate ancestors,” she adds. “Fiber keeps our intestinal flora healthy.”

Scientists have known that people living in urban areas have less microbial diversity in their guts than people living in rural areas. Because humans rely on gut microbes to break down dietary fiber from plants, the lower biodiversity may contribute to the increasing incidence of metabolic conditions in industrial societies.

To get new insights into the origins and evolutionary trajectories of cellulose-degrading gut bacteria named Ruminococcus, Moraïs and her colleagues examined their prevalence in diverse human populations.

Breaking down cellulose

The researchers identified previously unknown Ruminococcus species in the human gut microbiota, which they named Candidatus Ruminococcus primaciens, Ruminococcus hominiciens and Ruminococcus ruminiciens. All these bacteria are able to degrade cellulose, the building block of fiber.

Ruminococcus bacteria degrade cellulose by producing large protein complexes called cellulosomes. Cellulosomes attach to cellulose fibers and break them apart. Then, enzymes further disassemble cellulose fibers into shorter chains, which can be digested by not only Ruminococcus but also other gut microbes.

“Bottom line, cellulosomes turn fiber into sugars that feed an entire community, a formidable engineering feat,” says study co-author Ed Bayer at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, Israel.

Fiber diets

Ruminococcus species are common components of the gut microbiota in non-human primates, hunter-gatherer societies and people living in rural settings. These bacteria may have been prevalent in ancient human societies, with some strains likely originating in ruminants and later transferring to humans.

However, Ruminococcus are lacking in people living in industrial societies, the researchers found. This is likely due to diet shifts in industrial societies, which have moved away from fiber-rich foods typically produced on farms. These alterations may contribute to the decline of key cellulose-degrading microbes within their microbiota, the authors say.

The work suggests that ruminants and non-human primates might serve as sources for important cellulose-degrading Ruminococcus strains. The findings could also inform strategies to reintroduce Ruminococcus strains in the human gut through targeted diets and specialized probiotics, the authors say.