What is already known

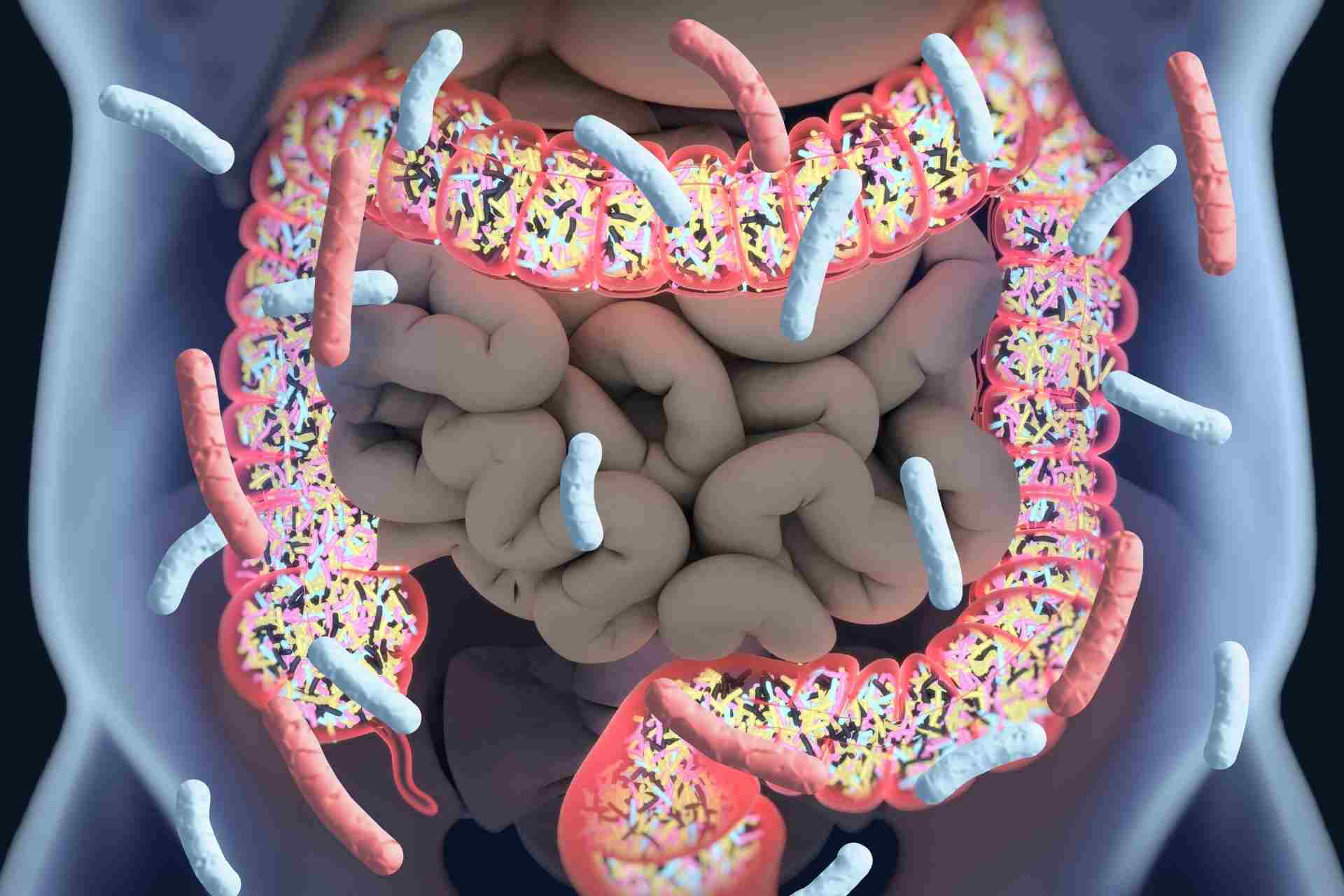

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an effective treatment for life-threatening infections of the gut, but its mode of action and how the microbiotas of donors and recipients interact is poorly understood.

What this research adds

Researchers analyzed clinical and metagenomics data from more than 300 FMTs, sampled before and after intervention. Their results suggest that the microbiota of the recipients, rather than that of the donors, determines the microbial mix resulting from FMT. The diversity of a recipient’s gut microbiota, as well as how different their microbiota is from a that of a donor, are major factors in determining which species will colonize the gut after FMT.

Conclusions

The findings may inform the development of more effective microbial-based therapies and help to identify recipients that could benefit the most from FMT.

Fecal microbiota transplantation is an effective treatment for life-threatening infections of the gut, but its mode of action remains cloudy. Now, researchers found that the microbiota of the recipient, rather than that of the donor, determines the microbial mix resulting from a fecal transplant.

The findings, published in Nature Medicine, may inform the development of more effective microbial-based therapies and help to identify recipients that could benefit the most from FMT.

“As our understanding of the ecological processes in the gut following FMT improves, we may discover more precise and more targeted links to clinical effects — for example, to displace only specific strains [for example, pathogens] while minimizing ‘collateral’ effects to the rest of the microbiome,” says study senior author Peer Bork at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory.

The idea behind fecal microbiota transplantation, or FMT, is that the gut microbes of a donor can help to modify a recipient’s microbiota in ways that promote health. But how the microbiotas of donors and recipients interact after transplantation is poorly understood.

To address this question, Bork and his colleagues analyzed clinical and metagenomics data from 316 FMTs used to treat ten different diseases.

Recipient effect

The researchers collected and analyzed samples before and after intervention, and they quantified the dynamics of more than 1,089 microbial species.

Previous work by Bork’s team showed that microbial strains from a donor and a recipient can coexist. This time around, the researchers found that the microbiota of the recipient, rather than that of the donor, determines the microbial mix resulting from FMT.

Some species, including Bacteroides, Blautia and Faecalibacterium were often found coexisting, whereas other species such Veillonella parvula, Akkermansia muciniphila and Prevotella copri were less likely to be found within the same host.

Colonization success

Next, the team assessed which factors determine how easily a donor’s microbiota can colonize a recipient’s gut.

The diversity of the recipient’s gut microbiota, as well as how different their microbiota is from a that of a donor, are major factors in determining which species will thrive after a transplant, the researchers found.

In a recipient’s microbiota, bacteria such as Bacteroidales were among the strongest inhibitors of colonization, whereas Lactococcus lactis, Streptococcus salivarius and Dialister invisus in the recipient were promoting colonization.

However, the researchers note, the colonization of the gut by individual species was predictable only in part. “This implies that colonization success may be stochastic to a large extent,” they say.