What is already known on this topic

Animals that hibernate, such as bears and ground squirrels, reduce their energy demands and use their fat reserves to meet their energy needs until spring. But it’s unclear how these animals get important nutrients and maintain muscle while hibernating.

What this research adds

By tracking the fate of nitrogen in hibernating ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus), researchers discovered that some microbes break down urea, a waste product that is usually excreted as urine, into nitrogen that can be used to build new proteins. This helps the squirrels to get key nutrients and avoid muscle loss during hibernation.

Conclusions

Understanding how gut microbes recycles urea could inform the development of microbiota-based therapies to mitigate muscle loss and nutrient depletion in conditions such as malnutrition and muscle-wasting disorders, but also in old age and even during extended space flights.

Mammals that hibernate, such as bears and ground squirrels, reduce their energy demands and use their fat reserves to meet their energy needs until spring. But it’s unclear how these animals get important nutrients and maintain muscle while hibernating. Now, researchers have found that microbes in the gut of ground squirrels recycle a waste product into building blocks to make proteins, helping the animals to survive a long winter without food.

The findings, published in Science, may help people with conditions such as malnutrition or muscle-wasting disorders. Understanding the role of gut microbes in hibernation could inform the development of microbiota-based therapies to mitigate muscle loss and nutrient depletion in these conditions, but also in old age and even during extended space flights.

Hibernation evolved to help some mammals survive periods, such as winter, characterized by scarcity of food. Hibernating animals slow their metabolism by as much as 99% and enter into a state of prolonged inactivity and starvation. This causes the body to break down muscle proteins and produce ammonium, which is concentrated into urea. Urea is usually excreted as urine in a process that leads animals to lose nitrogen, a key building block for amino acids and proteins.

Scientists have known that urea can be broken down by some gut microbes in the gut of hibernating ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus), but whether nitrogen from urea could help replenish the animals’ protein pool remained unclear. To address this question, researchers led by Hannah Carey and Fariba Assadi-Porte at the University of Wisconsin-Madison tracked the fate of nitrogen in hibernating squirrels.

Salvaging urea

The researchers produced urea labelled with isotopes of carbon and nitrogen and then injected it into the blood of squirrels. The injections happened at three stages: during summer — when squirrels are active, early during the squirrels’ hibernation, and late during hibernation. Some of the squirrels had an intact gut microbiota, whereas others were treated with antibiotics to kill off gut microbes.

The team found that some of the urea produced during hibernation was transported to the squirrels’ intestine. Many animals, including squirrels, do not have enzymes called ureases, which break down urea, whereas some gut microbes do.

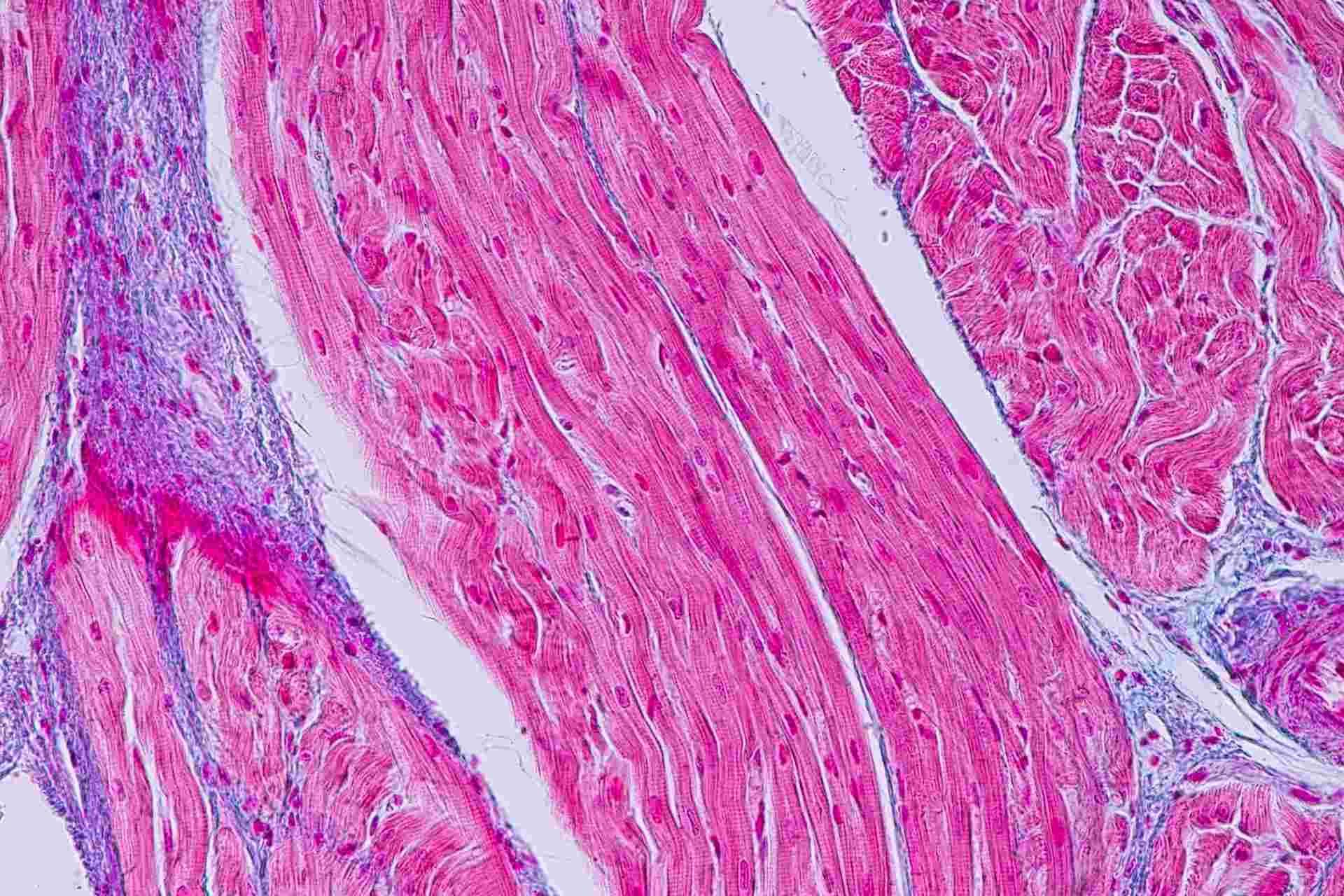

By tracking isotopically labeled nitrogen, the researchers discovered that gut microbes that are able to break down urea could incorporate nitrogen from urea into metabolites that were found into the squirrels’ muscles and liver. Squirrels without gut microbes didn’t have these compounds in significant amount in their muscles and liver.

Staying strong

Next, the researchers analyzed the contents of the squirrel’s cecum and found several urease genes in the animals with an intact gut microbiota. The levels of urease genes were higher in winter, albeit not significantly.

The findings suggest that gut microbes convert urea into nitrogen, which squirrels then use to make amino acids and build new proteins. This allows the animals to maintain a functional protein balance and preserve their muscles.

“Our results provide evidence that the gut microbiome plays a functional role during the hibernation season,” the researchers say. However, the findings could have implications that go beyond hibernation: understanding how ground squirrels and other hibernating animals maintain protein balance and mitigate muscle wasting could help develop approaches to preserve muscle in people affected by disorders involving the accelerated loss of muscle mass and function, the researchers say.