What is already known

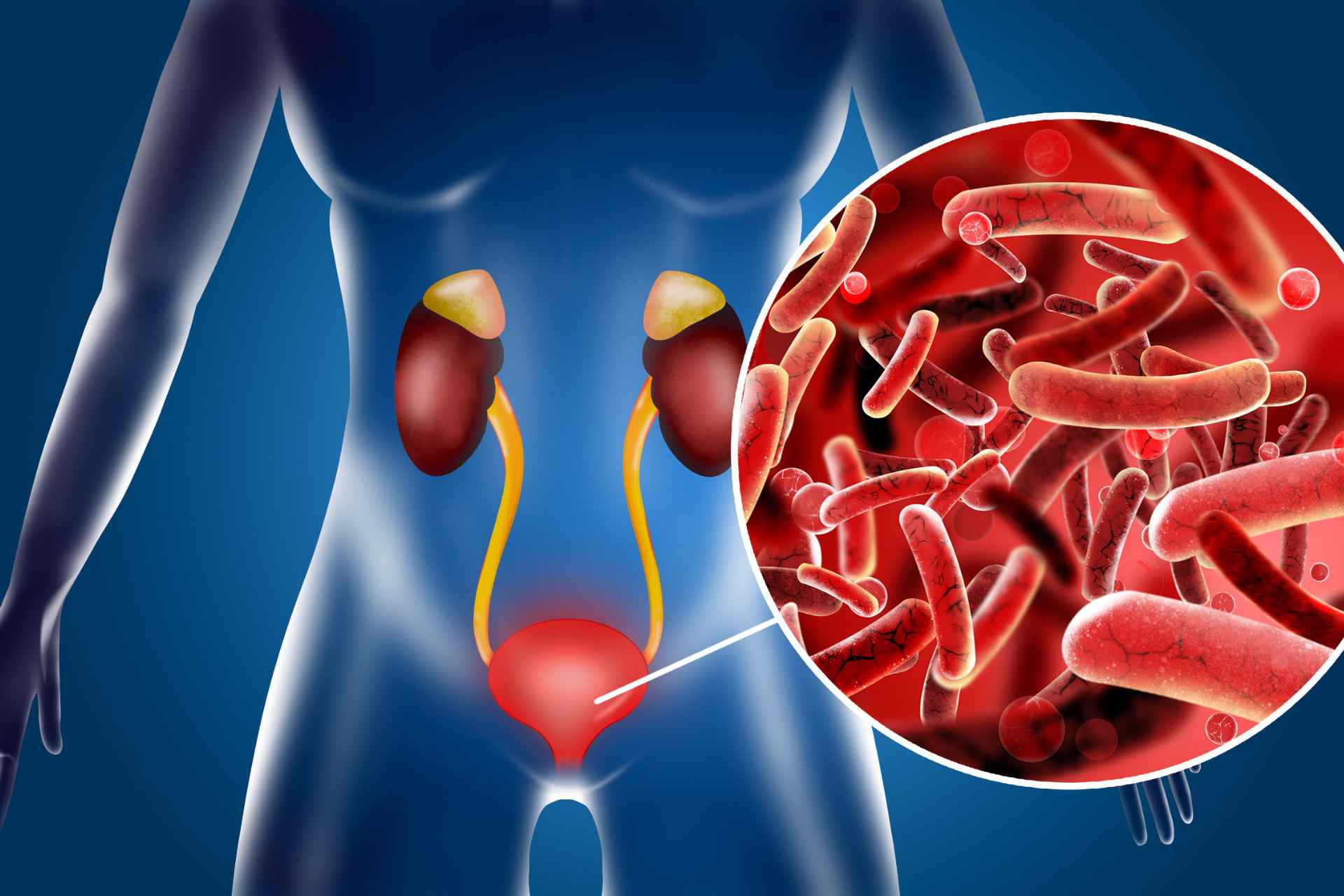

Urinary tract infections (UTIs), usually caused by bacteria from feces entering the urinary tract, are one of the most common bacterial infections in humans, with about 30% of people having a recurring UTI within six months. UTIs have been typically studied in animals and cultured cells, but it’s unclear how pathogenic bacteria interact with the human bladder during infection.

What this research adds

Researchers developed three-dimensional cell models that mimic the structure and function of human bladder tissue. Then, they exposed the ‘mini bladders’ to six bacterial species commonly found in real human bladders: Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Streptococcus agalactiae and Klebsiella pneumoniae. The team found that bacteria use different strategies, including forming pod-like structures within the bladder wall, to survive antibiotic treatment and hide from the immune system.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that effective treatments for recurrent UTIs may require the ability to penetrate human tissues, suggesting that current approaches to diagnosing and treating the infections may be inadequate for people who frequently suffer from them.

Urinary tract infections, or UTIs, affect about 400 million people worldwide every year. Now, working in artificial bladders, researchers have found that disease-causing bacteria use different strategies, including forming pod-like structures within the bladder wall, to survive antibiotic treatment and hide from the immune system.

The findings, published in Science Advances, suggest that current approaches to diagnosing and treating UTIs may be inadequate for people who frequently suffer from them.

“Some species of both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ bugs formed pods within the bladder wall, most likely as a way of surviving in this harsh environment,” says study senior author Jennifer Rohn at University College London. “If this happens with a friendly bug, this isn’t a problem. But if the bug is causing an infection, this poses a serious problem for diagnosis and treatment because the bacteria aren’t necessarily going to be detected in a urine sample or be in a position where oral antibiotics can reach them.”

UTIs, usually caused by bacteria from feces entering the urinary tract, are one of the most common bacterial infections in humans, with about 30% of people having a recurring UTI within six months. UTIs have been typically studied in animals and cultured cells, but it’s unclear how pathogenic bacteria interact with the human bladder during infection. To examine the behavior of pathogens in the human bladder, Rohn and her team developed three-dimensional cell models that mimic the structure and function of bladder tissue.

Mini bladders

The researchers exposed the ‘mini bladders’ to six bacterial species commonly found in real human bladders: Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Streptococcus agalactiae and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The team found that bacteria use different strategies to survive antibiotic treatment and hide from the immune system. For example, some bacteria — both commensals and pathogens — invaded cells, whereas others formed pod-like structures with other bacteria within the bladder wall.

“One of the key observations was the importance of persistence,” Rohn says. “If you want to be a successful pathogen, you have to have strategies that help you to survive treatment and hide from patrolling immune cells, which means you live to fight another day.”

Improving diagnostics

The researchers also found that pathogens triggered the production of immune molecules called cytokines and the shedding of the top layer of the bladder wall, whereas commensal bacteria colonized the bladder tissue without causing an immune response.

“Based on our results, next-generation diagnostics for UTIs could focus on identifying ‘bad’ bugs based on how the body responds, rather than trying to spot the presence of problem bacteria among the background noise of the microbiome,” says study first author Carlos Flores.

Finally, the team discovered that a specific cell-surface component of E. coli bacteria, called FimH, was required for the formation of bacterial communities within cells, but not for cell invasion. Because FimH is a popular target for the development of antibiotic alternatives to treat UTIs, this finding highlights the need to develop alternative drugs that target other bacterial components besides FimH, the authors say.