What is already known

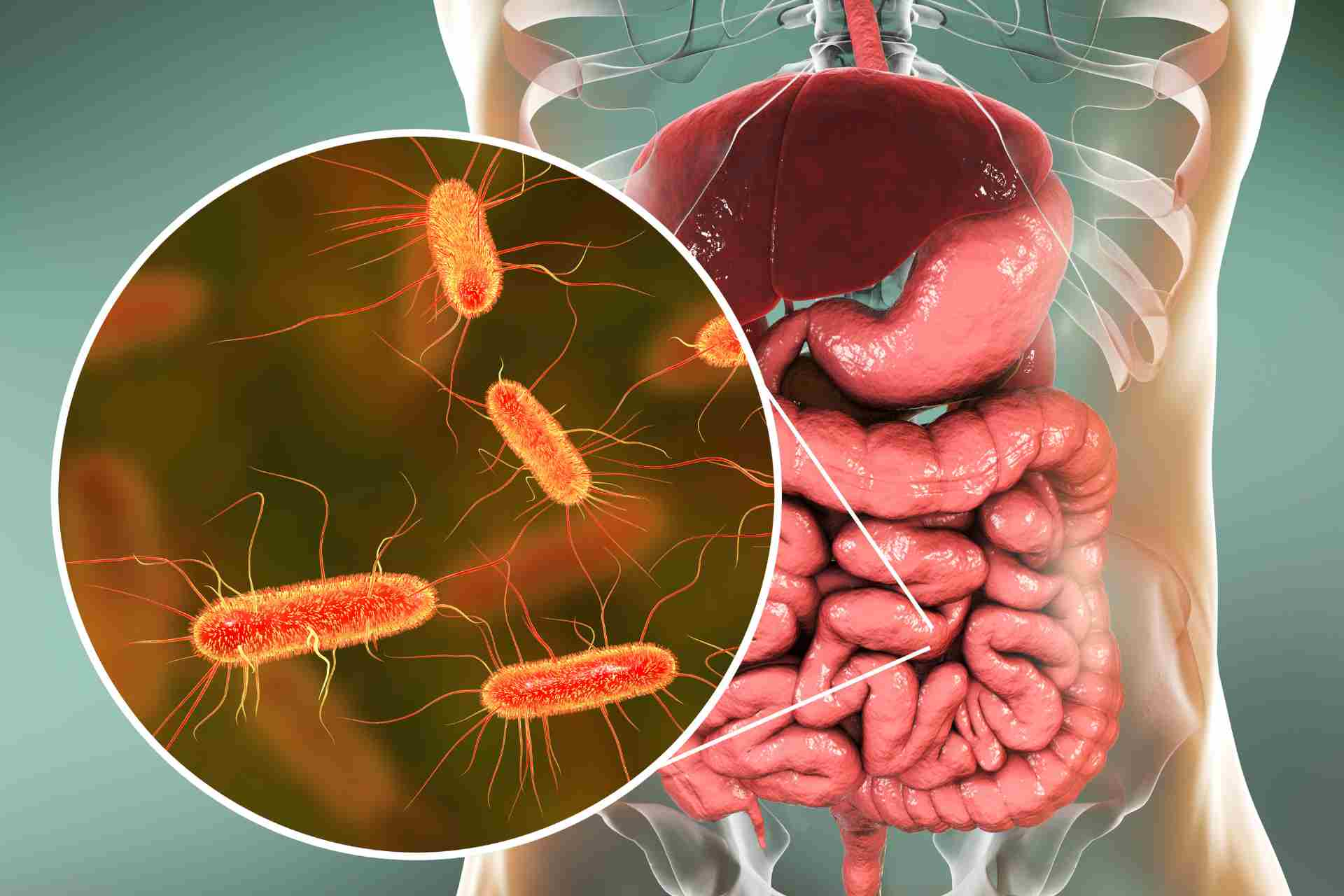

The microbiota of the last part of the small intestine, called the ileum, is distinct from that of the large intestine, or colon. However, not much is known about the ileal microbiota.

What this research adds

Researchers analyzed ileal samples from people who underwent surgery for cancer. The number of bacteria in the ileum depended largely on the host nutritional status: during fasting, the small intestine contained less bacteria, whereas after a meal, the bacteria bloomed again. The proportion of different subspecies of the same bacterial species changed quickly, within hours of eating a meal, the researchers found.

Conclusions

The study confirms that ileum and colon have a distinct microbiota, and indicates that, unlike the bacterial composition of the colon, that of the ileum is subject to frequent fluctuations.

The small intestine absorbs 90% of a person’s calories, but the composition of its microbiota has been difficult to pin down. New research shows that the bacterial composition of the last part of the small intestine — unlike that of the large intestine — is subject to frequent fluctuations.

The findings, published in Cell Host & Microbes, may help to better understand the development of intestinal disorders such as celiac disease and Crohn’s disease.

Scientists have known that the microbiota of the last part of the small intestine, called the ileum, is distinct from that of the large intestine, or colon. However, not much is known about the ileal microbiota. This is because the small intestine can only be reached during invasive procedures such as surgery.

Researchers led by Bahtiyar Yilmaz and Andrew Macpherson at the University of Bern analyzed 141 ileal samples from 79 people who underwent surgery for cancer. The team was able to peer at the ileum in real time through an artificial opening on the abdominal wall that is left after surgery once patients have healed.

Ileal microbiota

Although different people showed differences and fluctuations in microbial samples from their ileum, the researchers observed no overall differences after surgery compared with original ileal samples taken before surgery.

In general, Enterobacteriaceae and Bacilli were the most common bacteria in the ileum, whereas Bacteroidaceae, Prevotellaceae, Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae dominated in the colon. People with Crohn’s disease had an altered microbiota profile in both the small and large intestines, the researchers found.

The number of bacteria in the ileum depended largely on the host nutritional status: during fasting, the small intestine contained less bacteria, whereas after a meal, the bacteria bloomed again. The proportion of different subspecies of the same bacterial species changed quickly, within hours of eating a meal.

Bacterial ecosystem

In contrast to the rapid changes happening at the level of the ileal microbiota, small metabolites only showed minor differences in the small intestine after a meal, the researchers found.

“We think of these changes in the intestinal bacteria in the small intestine as an ecosystem,” Macpherson says. “Because the system is so flexible, each bacterial species can adapt to a changing environment in the small intestine by changing the proportions of subspecies and thus prevent the species as a whole from dying out.” This prevent bacterial species from going extinct in the small intestine, unless there are ‘bottlenecks’ due to illness, malnutrition or environmental pollution, Macpherson adds.

The findings may inform the development of therapeutic approaches for intestinal conditions including celiac disease and the long-term inflammation of the large intestine, the researchers say.